Outlines for a New Chronology of Ancient Jewish History

For many centuries, numerous attempts have been made to answer questions concerning the origin of the Jewish Bible, its authenticity, and its value as a historical source. The "Traditional Chronology" of ancient Jewish history from the Biblical period has presented a serious conundrum for historians seeking to reconcile existing information sourced from well- known Biblical books with the rapidly growing archaeological database. This current paper attempts to address some of these issues with a radical approach that moves the traditional timeline forward by almost 250 years. This "New Chronology" inevitably leads to a significant reconsideration of the validity of the events and historical figures described in the Bible.

1. Josephus Flavius and the Origin of the Traditional Chronology

Josephus Flavius

The Traditional Chronology of ancient Jewish history that is generally accepted today was first postulated by Josephus Flavius in his book - The Jewish Antiquities. Josephus, a Jewish historian writing in the Roman period, during the late-1st century AD, sought to celebrate the characters mentioned in the Bible, and by dating the events as far back in history as possible, he was able to idealize Jewish history and present the Jews as an ancient nation. Although he had access to the books written by the Greek historians from the Classical period, with accounts about of the Persian kings and their wars with the Greeks, these sources did not contain any material relating to the history of the Jews from before c. 300 BC. Josephus was apparently totally unaware of any Persian historical sources and relied on limited access to the Greek literature of the Hellenistic period that did not pay much attention to the subject of the Jews.

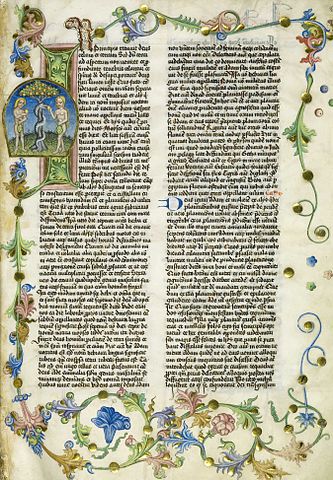

A leaf from the "Jewish antiquities"

In response to his contemporary critics, Josephus acknowledged that when he wrote his book, he had relied on the Biblical Books of Kings as his primary source of information concerning ancient Jewish history. He, therefore, described the historical events exactly as they were recorded in the Bible and presented their chronology according to his understanding of their sequence. Following Josephus's timeline, it has been widely accepted that the end of the Kingdom of Judea and the exile of the majority of its population was caused by the military actions of the famous ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Kingdom, King Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BC). Since the Bible states that the two exiles of the Judeans by the Babylonians occurred in his seventh and eighteenth years, with the destruction of the Temple happening in his nineteenth year, the exiles have been dated to 598 and 587 BC and the destruction of the Temple to 586 BC.

Information relating to the return of the Jews from the Babylonian exile and their subsequent rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem is contained in the Biblical Books of Ezra and Nehemiah. The Book of Ezra recounts that the first group of Jewish returnees from Babylon arrived with the Persian Governor of Judea, Zerubbabel, and Priest Joshua, and that they started rebuilding the Temple in the second year of King Darius’ s reign. The Book of Nehemiah preserves the text of the Memoirs of Nehemiah, an original account of his building activities in Jerusalem, written in the first person by Nehemiah himself. Nehemiah, who was appointed by the Persian King Artaxerxes to be the Governor of Judea, came to Jerusalem from Susa in the twentieth year of his reign, accompanied by a group of Persian Jews. Another group returned from Babylon with Ezra during the seventh year of King Artaxerxes’s reign. Although the figures of Nehemiah and Ezra were placed in the same timeframe by the later editor of the Book of Ezra-Nehemiah, which of them came first remains a subject of debate.

Josephus positioned the return of the Jews in the early Achaemenid period, placing Zerubbabel in the reign of King Darius I (522-486 BC), and Ezra and Nehemiah in the reign of King Xerxes (486-465 BC). Incidentally, the name of Xerxes is not mentioned in the Biblical text, but he was certainly known to readers of The Histories by Herodotus, that cast serious doubt on the identification of the Biblical king Artaxerxes as the Achaemenid King Xerxes. Dating the Babylonian exile and the Temple's destruction to the beginning of the 6th century BC has been almost universally accepted by scholars but, despite numerous attempts, establishing an accurate date for the return of the Jews has proved more elusive. Many scholars have chosen later dates, such as the reigns of King Artaxerxes I (465-424 BC) or King Darius II (423-404 BC), and thus attempts have been made to fix the dates of Nehemiah's and Zerubbabel's arrivals in the years 445 and 422 BC, respectively. More recently, however, other scholars have started to question the historicity of the return itself. By placing the characters and the events described in Ezra-Nehemiah in the early Achaemenid period, Josephus created a significant chronological gap between the middle of the 5th and the beginning of the 2nd century BC, not only in Jewish history but also in Jewish literature. This apparent dearth of information, from the return of the Jews right up until the Seleucid conquest of Judea in 200 BC, creates an exceptionally lengthy period for the ancient Jewish "Dark Ages". It is hard to believe that no significant events whatsoever occurred in Judea during this entire period; it is even more difficult to accept that the Jews stopped recording their own history for almost 250 years!

2. A Challenge to the Traditional Chronology

Photographer: Donna Foster Roizen. Copyright holder: Frederic Jueneman [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Immanuel Velikovsky

The chronology of ancient Jewish history that Josephus put forward was not unanimously accepted, even in ancient times. For example, in the 2nd century AD, a rabbinical chronicle, Seder Olam Rabbah, presented a different chronological order and stated that the Persian period lasted for 34 years and that the Second Temple of Jerusalem had stood for 420 years. An Egyptian scholar, Apion, wrote a book that disagreed with Josephus's chronology, and Josephus responded with his booklet Against Apion. In general, however, modern scholars of Jewish history have continued to use Josephus’ chronology, thereby maintaining the traditional timeline.

This Traditional Chronology was first challenged by Immanuel Velikovsky an American scholar of Russian Jewish origin, in his book entitled, Ages in Chaos, first published in New York in 1952 (36). Velikovsky suggested an alternative approach for examining the chronology of the history of the Ancient Near East and proposed reviewing the entire history of the region using the concept of "ghost-doubles" or alter-egos. These were historical figures that appear with different identities in different sources; they were thought to have lived in different periods but were, in fact, the same people with the accounts and events concerning them wrongly dated by previous generations of scholars. This approach allowed him to propose a "short" chronology of ancient Egyptian history, bringing forward the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt by about six hundred years and setting the timeframe of the Exodus in the 10th century BC, and the United Monarchy of Solomon in the 8th century BC. In this way, Hatshepsut, the Queen of Egypt from the Eighteenth Dynasty, became a contemporary of King Solomon, and could be identified as the Queen of Sheba.

More recently, a British Egyptologist, David Rohl, revisited the available Egyptian sources and created a New Chronology of Ancient Egypt; he attempted to match the chain of events described in the Bible with available archaeological data and to identify some of the Biblical characters with people whose names appear in archaeological finds (31). He suggested removing the period of the "Dark Ages" of Egyptian history by re-dating the historical events and bringing them forward from the 13th century BC to the 10th century BC. He also re-dated the Egyptian kings of the 19th through the 25th Dynasties, bringing forward the conventional dating by about 300-350 years, and equating the Biblical figure of the Egyptian Pharaoh Shishak, who sacked Jerusalem after the death of King Solomon, with Ramesses II of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

Another theory was developed by the German scholar Gunnar Heinsohn who proposed radically re-dating the entire Neo-Assyrian period, the 9th-7th centuries BC (20). He based his conclusions on a positive identification of Neo-Assyrian rulers with the Persian kings of the Achaemenid period. Using observations of the stratigraphy of many archaeological sites in North Mesopotamia, he noted that the "Achaemenid" stratum is entirely missing from these, and thus came to the controversial conclusion that the "Neo-Assyrian" period should be equated with the "Achaemenid" period. The British historian Emmett Sweeney continued with a similar theory, arguing that all the rulers known in history as Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian kings were, in fact, the Great Kings of the Persians under the guise of Mesopotamians (35). He proposed that Tiglath-Pileser III should be identified with Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid dynasty, and that the Neo-Assyrian and the Neo-Babylonian kings who followed him should be identified with the Achaemenid kings who succeeded Cyrus: thus Shalmaneser was equated to Cambyses; Sargon to Darius I; Sennacherib to Xerxes; Esarhaddon to Artaxerxes I; Ashurbanipal to Darius II; Nabopolassar to Artaxerxes II; Nebuchadnezzar to Artaxerxes III; and Nabonidus to Darius III. Assuming the timeline of Sweeney is correct, it would follow that the Jews were taken to Babylon by Artaxerxes III Ochus, shortly before the destruction of the Achaemenid Empire. If this is the case, when did they return from the exile and what were the identities of the Persian kings, Artaxerxes and Darius, mentioned in Ezra-Nehemiah?

While most Israeli historians have remained faithful to the traditional timeline, some archaeologists, including Israel Finkelstein from Tel Aviv University, are more sympathetic to re-evaluating the conventional chronology. Finkelstein claims that none of the ancient sites of Northern Israel preceded the 9th century BC and that the United Monarchy of David and Solomon that was traditionally dated to the 10th century BC, is a myth (12). More recently, Finkelstein published a series of studies collected in his book, Hasmonean Realities Behind Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles (13), where he proposed a radical re-evaluation of Biblical research by suggesting a Hellenistic setting for the historical events that are revealed from an analysis of these Biblical books. While recognizing that large parts of these books are of Hellenistic origin, and were presumably inserted into the older texts, for some reason he refrained from pursuing this argument further and admitting the possibility that the entire texts, and their heroes, could have been of the Hellenistic period. Could it have been a similar situation with the Biblical narrative relating to Kings David and Solomon?

3. Was there ever a United Jewish Monarchy?

The primary sources of our knowledge of the ancient Jewish history are the 2 Books of Samuel and the 2 Books of Kings, all of which were initially composed as one book and then separated at a later stage. Samuel tells the story of the Prophet Samuel in the context of the history of the "House of David" that replaced the "House of Saul". The reign of the first ruler of Judea, King Saul, has been traditionally placed by scholars in the 11th century BC. However, the inclusion of references that are thought to be anachronistic, such as the mention of chariots that did not exist before the 8th century BC, led to the suggestion that the core narrative of Samuel could have been written later, and can be used to reconstruct the history of the Kingdom of Saul if this come into being sometime in the middle of the 8th century BC. 1 Kings continues the narrative of Samuel and celebrates the period of the United Monarchy that was established after the death of King David by his son, King Solomon; it suggests that this was a period of outstanding prosperity, which was followed by a period of devastation and disorder. The narrative of Kings presents the ancient period of Jewish history as the history of two competing states – Israel and Judea – both emerging from the tragic break-up of the United Monarchy after the death of Solomon. Following the disintegration of the United Monarchy, the Kingdom of Israel was created in the north and the Kingdom of Judea was established in the south, around Jerusalem. According to the Traditional Chronology, both Kingdoms came into being c. 930 BC, and although Northern Kingdom ceased to exist in 722 BC, the Southern Kingdom survived until 587/6 BC.

During the last few decades, Israeli archaeologists have carried out extensive excavations of many ancient sites. One of the most fascinating results is the total absence of archaeological layers that can be securely dated to the period from the 10th century BC, the traditionally accepted timeframe for the United Jewish Monarchy. The large public structures which have been excavated in the towns of Northern Israel only date from the 9th to the mid-8th century BC and provide examples of architecture of the Kingdom of Israel, but there is no trace of large government buildings that could possibly be associated with the supposed reigns of either King David or King Solomon (11; 12). These excavated structures are believed to have fallen out of use and to have been abandoned as a result of the Assyrian invasion of Northern Israel that occurred in 733/2 BC, and brought an end to the Kingdom of Israel, although there is no definitive evidence to support this conclusion as the kings of Israel left no records similar to the monumental cuneiform inscriptions of the Assyrian kings.

It is, perhaps, strange that the earliest epigraphic evidence of Judea as an independent political entity comes from Assyrian inscriptions from the time of Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727 BC); these include a brief mention of Judea in the lists of the small kingdoms of the Eastern Mediterranean that were subjected to the power of the Assyrian king, in the same way as the Phoenician town-states that paid him tribute (16b). Assyrian cuneiform inscriptions of the 9th-8th centuries BC, however, do mention a political entity in Northern Israel that is often referred to as the "House of Omri". According to 1 Kings 16, King Omri was the sixth King of Israel; although he was a successful military campaigner who extended the borders of his Kingdom, he was still considered to have been an "evil" king. Clearly, for the Judean chronicler, the long-since destroyed Kingdom of Israel was no more than a "sinful kingdom"; none of its kings displayed positive characteristics, and none were worthy of God’s favour. This negative stance may be explained by their comparison to the chieftains of the Samaritans, who were contemporaries of the Judean chronicler and, as can be seen in Ezra-Nehemiah, were the primary competitors of the Judeans. This is probably why the Judean chronicler, who recorded that the city of Tirzah in Northern Israel was the capital of Omri, credited him with the construction of Samaria, which he apparently made his new capital (1 Kings 16:24). Although Thomas Thompson and Niels Lemche suggest that Omri may be a dynastic name indicating the apical founder of the Kingdom of Israel rather than denoting an actual historical king, Lester Grabbe showed that there is no reason to question the historicity of Omri, himself (17, p. 48-49). Nevertheless, his relation to Samaria remains in doubt, and the "Samaritan" identity of the ancient Israelite kings can be questioned.

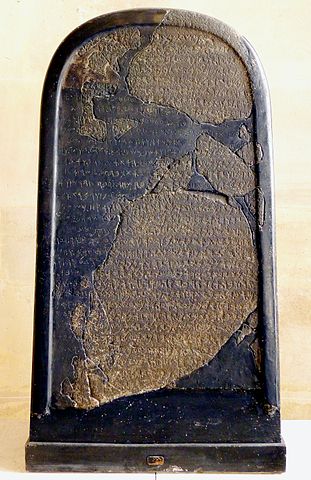

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser

The events recounted in Kings relating to the history of Israel can only be regarded as of historical value if they can be confirmed by extra-Biblical sources. In this connection, the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III shows Jehu, the son of Omri, bringing tribute to the Assyrian king, proving that the Omrides fell under Assyrian power. The Mesha Stele, a monument set up by King Mesha of Moab, bears the most extensive inscription ever recovered in the region that specifically refers to the "House of Omri" as Israel. It recounts how Moab was oppressed by the "King of Israel, the son of Omri", and describes Mesha's victories over him. While Mesha makes no mention of Judea, 2 Kings 3 artificially brings the King of Judea, Jehoshaphat, into the story and allies him with Jehoram of Israel. This story is an example of the methods used by the author of Kings who deliberately attempted to establish the kings of Judea alongside those of Israel.

The Books of Kings must be viewed in the context of the Hellenistic historical tradition; they appear to be a very complex compilation resulting from the merging of two different categories of written sources. On the one hand were the Jewish chronicles that kept a lists of the names of the kings and the length of their reigns; on the other, the Mesopotamian cuneiform sources that evolved into the Babyloniaca, the "History of Babylonia", composed by the Seleucid Priest Berossus, and published around 278 BC. Many excerpts from this treatise are scattered among the ancient texts, such as those of Josephus, and the Greek historian Eusebius of Caesarea. It is interesting that Berossus paid attention to the Assyrian King Sennacherib and to the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar who was considered a model ruler by the Seleucid kings (22). Berossus' achievement may be seen in terms of how he combined Greek methods of historical narrative with the cuneiform accounts to form a unique composite that allowed him to skip the Achaemenid period in the history of Mesopotamia while focusing on the continuation between the Babylonian and the Seleucid kings.

While the methods used in Kings appear to be similar to those employed by Berossus, his ideas and his language appear to be closer to those of the Deuteronomist, the author of the Fifth Book of the Torah. While the latter focused on the unification of the cult and the centrality of Jerusalem, the former dealt with the reflection of the catastrophe that befell the Jewish nation when its Kingdom was destroyed and most of the population was sent into captivity. Kings not only accepted the timeline of Berossus’ Babyloniaca, but by using two separate lists – one detailing the kings of Israel and the other the kings of Judea – he aligned their dates in an artificial attempt to establish historical events concerning both kingdoms within the same timeframe. This approach has presented serious obstacles for historians due to the resulting inconsistencies. For example, Omri’s accession to the throne of Israel in the 31st year of Asa of Judah (1 Kings 16:23) cannot have followed the death of his predecessor Zimri in the 27th year of Asa (1 Kings 16:15). Likewise, questions arise in respect of the attempts in Kings to demonstrate the supremacy of Judea over Israel by presenting the idea that the United Monarchy, which predated the Kingdom of Israel, was centred in Jerusalem, from where it apparently ruled over the entire Land of Israel. Indeed, the current state of archaeological research supports neither the idea of the United Monarchy nor the simultaneous existence of the two kingdoms competing with one another during the same period; comparative analysis of the sources suggests that the Kingdom of Judea flourished immediately after the downfall of the Kingdom of Israel.

4. Did the Kings of Judea - Saul, David, and Solomon - ever exist?

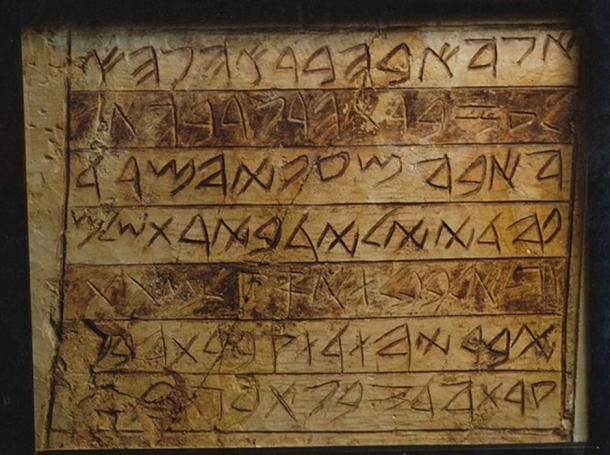

The absence of any mention of the great Judean Kings, David and Solomon, in contemporary Assyrian and Egyptian sources has added more weight to the sceptical voices questioning the existence of the United Jewish Monarchy. The rise to power of King David, King Saul’s former favourite who betrayed him but later become his successor, is described in 2 Samuel. At first, King David ruled from Hebron but after he defeated the Jebusites he established his capital in Jerusalem. There is no firm archaeological evidence, however, to establish the dates for his reign. Excavations in Kiryat Ye’arim (the place where the Ark of the Covenant was placed by King David for safekeeping), in Hebron (the early seat of King David), and in Jerusalem (the capital city and the site of the future Solomonic Temple) have shown that all these places were, effectively, small, sparsely populated villages until the second part of the 8th century BC. Moreover, as no personal seals, bullae, or ostraca with Paleo-Hebrew inscriptions similar to these found in the settlements of Northern Israel have survived in the territory of Judea prior to that time, there is no clear evidence of a significant Jewish presence either in Jerusalem or in other Judean cities during the previous period.

The discovery of the Tel Dan Stele in 1993 might change this situation. It bears a fragmentary Aramaic inscription telling of the victory of the King of Aram, who was appointed by King Hadad, over the "King of Israel"; it also occasionally mentions his fight with bytdwd – the "House of David" (5). Many scholars have decided that this inscription might be considered conclusive evidence of the existence of the historical figure of King David. The generally accepted date for the events mentioned in the Tel Dan inscription is 9th century BC, and this inscription was suggested by Lester Grabbe that it belonged to the Aramaean King Hazael, who according to 2 Kings 8:27-29, fought with Jeroboam, King of Israel, and his ally, King Ahaziah of Judea (17, p. 54-55), however, this does not explain the reference to Hadad. In my opinion, Tel Dan Stele may refer to King Hadad the Edomite who appears to have been one of the main adversaries of King David; 1 Kings 11:14-25 relates that after the death of King David he reclaimed the throne of Edom, abhorred Israel, and reigned over Aram-Damascus. It follows that the Tel Dan inscription could have been written on behalf of his ally, King Hadadezer of Zobah, an Aramaean Kingdom in the Beqaa Valley of Lebanon, who reigned in the time of King David (2 Samuel 8; 1 Kings 23). It appears that this inscription can be dated from the period of mid-8th century BC, when the Kingdom of Israel still existed, which is why the conflict of the Aramaeans with the "House of David" is mentioned there.

LMLK seal impression

The process of King David’s founding of Jerusalem as his new capital, must potentially have led to a massive supply of goods for the king’s court. This can be reaffirmed by many fragments from large storage jars that have been found in different cities of Judea, mainly in Lachish and Jerusalem. Dating from the second part of the 8th century BC, these have handles that were stamped with l'mlk, "for the king" and bear an image of a winged sun, a symbol of royalty in ancient Near Eastern cultures. Among them was a group with the handles sealed with l'mlk hbrn, "for the King of Hebron", confirming that David ruled Hebron prior to his conquest of Jerusalem.

Russell Gmirkin showed that the Acts of Solomon, the description of King Solomon’s activities in 1 Kings 3-11, drew heavily on the royal inscriptions of the 9th-century BC Assyrian King Shalmaneser III (16B), but although this could point to the access of Kings to the Assyrian records, it does not necessarily follow that King Solomon’s existence must be denied. Is there another way to verify the authenticity of the account in 1 Kings 6 concerning King Solomon’s building of the Temple? There is yet one more important historical personage who has been ignored by scholars – Hiram, the Phoenician king of Tyre. There was certainly a king of Tyre named Hiram who reigned in the 740s-730s BC and was listed as a tributary of the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III in 738 BC. According to 1 Kings 5:1-11 and 9:10-14, Hiram became the main ally of King Solomon, sending him architects, workman, cedar wood, and gold for the building of the Temple.

The Assyrian conquest of the eastern Mediterranean in the 730s BC did not prevent the king of Tyre from exploiting his own economic opportunities. A Phoenician inscription from Cyprus confirms Hiram's control over the city of Kition (Larnaka) and his ownership of copper mines located on the coast. In addition, the Paleo-Hebrew inscription on a pottery shard found in Tel Qasila (modern Tel Aviv) and dated to the 8th century BC, noted goods sent from the "Land of Ophir" to Beit-Horon. Is this a parallel to the famous account in 1 Kings 10 concerning the joint maritime expeditions of Kings Hiram and Solomon organized to the Land of Ophir, where gold, silver, stones, and algum wood were all to be found? A letter of Qurdi-Aššur-lāmur to Tiglath-Pileser III, quotes a report from the Assyrian functionary Nabū-šēzib in Tyre, where he claims to have prevented Hiram from seizing a sacred tree from Sidon (25, pp. 185-8). Is this story of the attempted felling of a tree related to Hiram’s help in supplying the cedar trees used for building the Temple? If so, this suggests that both King Hiram and King Solomon were active at approximately the same time, and that the process of the construction of the First Temple began in the 730s BC.

5. When did the Exile of the Israelites and Samaritans take place?

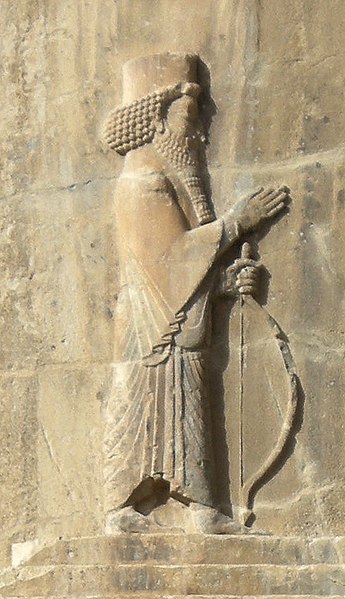

Tiglath-Pileser III

The destruction of the Kingdom of Israel came about because of two attacks by the Assyrians both described in 2 Kings. 2 Kings 15:29 relates that the first attack was carried out by Tiglath-Pileser III and resulted in the defeat and death of King Pekah from the House of Omri and the capture of a number of cities including Ijon, Abel-beth-Maachah, Janoah, Kedesh, Hazor, Gilad and Galilee, including the Land of Naphtali; most of the inhabitants were sent into exile in Assyria. This first attack was mentioned in the Assyrian inscriptions which record that the Assyrians had Pekah removed for disloyalty and replaced him with Hoshea. These events are arguably set around 733 BC, at the same time that Tiglath-Pileser III conquered Phoenician cities, took Damascus, and exiled many Aramaeans.

1 Kings 9:13 reports that, as repayment for King Hiram’s help, King Solomon handed him the district of Kabul, which contained the "empty towns" of Galilee. Bearing in mind that after the invasion of the Assyrians into north-west Galilee in 733/2 BC there was a great deal of devastation to that area and the towns of Northern Israel were left empty; this would seem to suggest that the area was transferred to Hiram around 730 BC. But what happened to the Israelites who were not deported by the Assyrians? The best answer is that they established Samaria, which became a new hub in the central highlands; however, it is also possible that some people were able to flee south to the sub-mountainous areas that surrounded Jerusalem. If this was the case, the significant shift in the demographics of Judea during the last third of the 8th century BC might have happened due to the mass migration of the Israelites. The fact that both the Samaritans as well as the Judeans continued to use the same Paleo-Hebrew script that at first spread in the North, is strong evidence of their ethno-cultural continuity.

The account in 2 Kings 15:30 does not end with the death of King Pekah but goes on to describe the rise to power of King Hoshea, the son of Elah (732-23 BC), who was apparently unrelated to the Omrides dynasty. The second Assyrian attack on Samaria, launched by King Shalmaneser, is also described in 2 Kings 17:1-5. The city of Samaria was besieged after the Assyrians discovered that Hoshea had been sending gifts to the Egyptian King So, who was identified as Pharaoh Osorkon IV (730-15 BC). His help never materialised, and after the fall of Samaria, Hoshea was imprisoned. The next verse adds that an Assyrian king sent the Samaritans into exile in "Halah and in Habor by the river of Gozan, and into the Median cities". These people, lost in captivity, became known as the Ten Lost Tribes.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

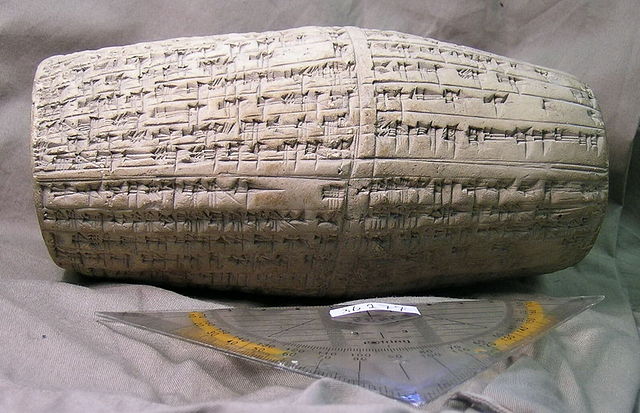

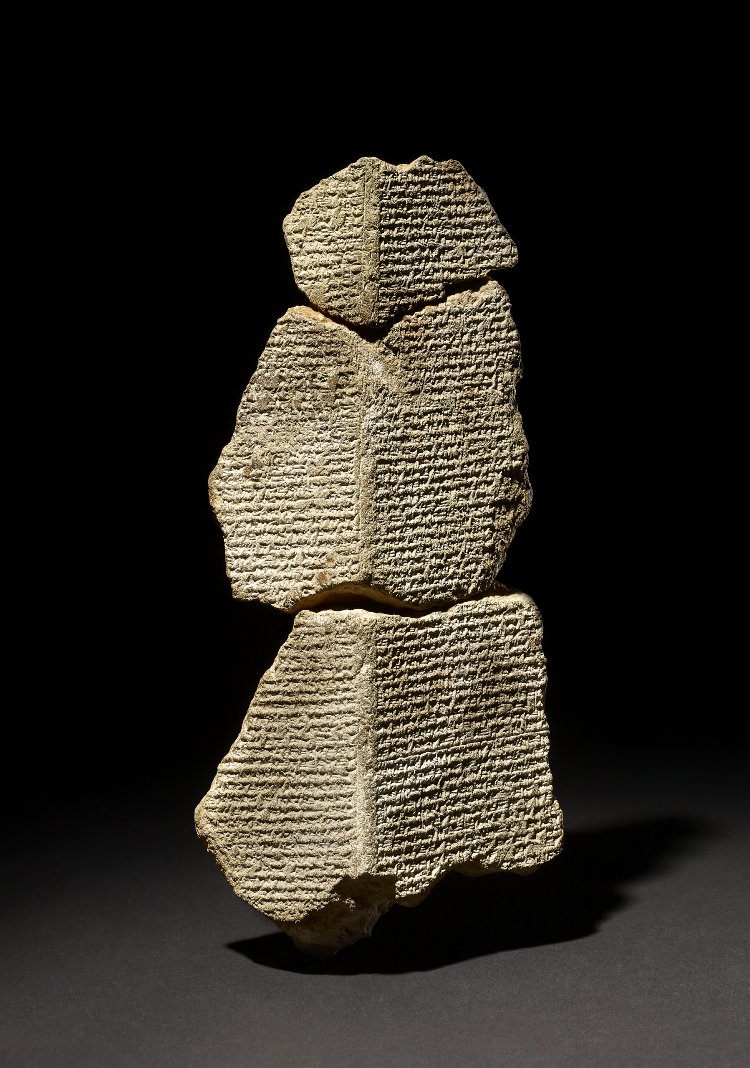

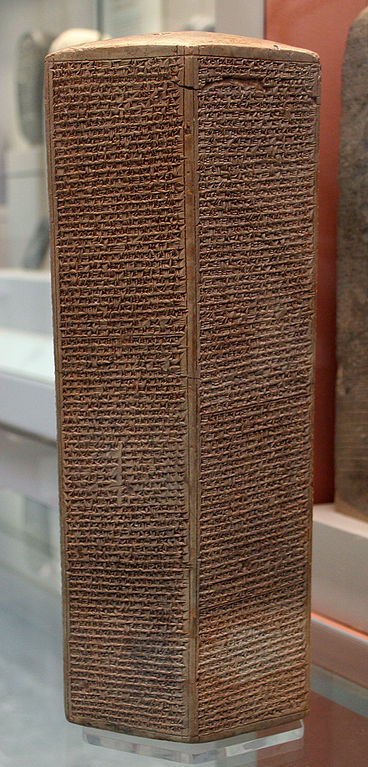

Fragment of a clay prism with Annals of Sargon II

The Traditional Chronology dates the deportation of the Samaritans to 722 BC, the last year of the reign of King Shalmaneser V (727-722 BC), which corresponds to the data of the Babylonian Chronicle I:1:28 stating that Shalmaneser V "ruined" Šamara’in (Samaria). However, as no mention of the Samaritan exile has been found in inscriptions from the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, it has been suggested that any involvement of Shalmaneser V in these events can be regarded as speculative (40). The events relating to the fall of Samaria were recorded in eight cuneiform sources, all authorized by King Sargon. The Annals of Sargon were recorded on a clay prism and recounted that, in the beginning of his rule, after the conquest of *Samarina, some 27, 290 people were deported. The inscription from a stele in the castle of Khorsabad claimed that, in his seventh year King Sargon brought new settlers into Samaria who originated from different Arab tribes. This contradicts 2 Kings 17:24, which relates that the colonists arrived from the cities of Babylon, Cuthah, Avva, Hamath, and Sepharvaim. Surprisingly, no mention of King Sargon, the king of Asshur, has ever been found in Nineveh, with the result that for a very long time he was unknown. His name was, however, briefly mentioned in Isaiah 20:1-2 in connection with the Assyrian General Tartan’s capture of Ashdod. Although there is no evidence in the Bible to connect the expulsion of the Samaritans with Sargon II, the information from the Annals of Sargon has been commonly accepted as proof that he did, indeed, send the Samaritans into exile. It would seem more likely, however, that the data recorded by Sargon relates to historical events that occurred in some later period.

What was the identity of the king who ordered the exile of the Samaritans? Although Sweeney suggested identifying Sargon II with the Achaemenid King Darius I the Great, who reigned in 522 - 486 BC (35, p. 123-7), in my opinion, Sargon is the dynastic name of the Achaemenid King Xerxes (486-65 BC) and honours the ancient legendary king of Akkad, Sargon I; this would mean that the events relating to the fall of Samaria took place in the seventh year of his reign. After the excavation of Khorsabad Castle, it was suggested that it had once belonged to the Assyrian King Sargon II, although it would seem more likely that the castle of Khorsabad, in fact, belonged to Xerxes, as no other archaeological traces of this great king were found in the excavations of the Achaemenid capital Persepolis. This identification has led to the suggestion that the narrative of 2 Kings conflates memories of two different events: one – the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel that occurred in the Assyrian period, and the other – the conquest of Samaria that took place in 479 BC, in the Achaemenid period.

6. When were the reigns of Hezekiah and Josiah, the Kings of Judea?

According to 2 Kings 18, King Hezekiah was the fourteenth king of Judea, and the only one after the ancient great kings of the United Monarchy, David, and Solomon, to be praised for his activities. He is also the first ruler of Judea known from both Biblical and extra-Biblical sources. Unless the authenticity of a unique bulla belonging to his father is accepted, the earliest surviving epigraphic evidence of the existence of the kings of Judea dates from the time of King Hezekiah, the son of Ahab. During the past few decades, several bullae of Hezekiah have been found and published. They are inscribed in the Paleo-Hebrew script and depict an image of a winged sun, a symbol of royalty in many ancient cultures of the Near East, and mention Hezekiah's name; he is referred to on these as melech, "king", thus providing decisive evidence of his independent power.

Private Collection, London

Assyrian Relief from Sennacherib's castle, showing Jews of Lachish taken into captivity.

2 Kings 18:9-12 relates to the beginning of the twenty-nine-year reign of King Hezekiah, who reportedly become king in Hoshea’s third year; this coincides with the period of the Assyrian destruction of Samaria which is said to have begun in the fourth year of Hoshea’s reign, lasting until his sixth year. While the Traditional Chronology places these events in 722 BC, this is contradicted by the statement in 2 Kings 18:13 regarding the invasion of Judea led by Sennacherib in the fourteenth year of Hezekiah which according to the Assyrian inscriptions, happened in 701 BC. If so, the events of 701 BC would have taken place in Hezekiah’s twenty-fifth year, not his fourteenth. The narrative in 2 Kings that begins with the conquest of Lachish, an important Judean town, can be confirmed by the Lachish Reliefs set on the walls of Sennacherib's castle, and now kept in the British Museum; additionally, archaeological excavations on the site of Lachish appeared to verify this date for the Assyrian destruction of the city. 2 Kings 18:13-16 continues with another, unrelated, story of the siege of Jerusalem by the Assyrian army. Among Assyrian clay documents there are three hexagonal prisms that are inscribed with the same text recording Sennacherib’s military campaigns, the so-called Sennacherib's Annals. They all contain similar accounts but only one, the Taylor Prism, now in the British Museum, mentions Sennacherib’s interactions with Hezekiah with an account of his successful campaign launched against Jerusalem. According to this, the Judean king was confined to the city "like a bird in a cage", and despite having paid tribute, 200,000 Judeans were sent into exile. Although this story is believed to parallel the Biblical account, it seems likely that the unprovenanced Taylor Prism is one of several mid-19th century fabrications attempting to corroborate the Biblical narrative.

Taylor Prism

2 Kings 18:17-19 gives an account of King Hezekiah’s heroic resistance to the Assyrian invasion of Jerusalem. It reports that King Hezekiah protected Jerusalem with the reputed help of God's Angel who, in one night, managed to kill the entire Assyrian army besieging the city. This account concerning Hezekiah's heroic resistance to the Assyrian invasion might be an attempt by the author of 2 Kings to glorify the period of his reign in ancient history. In his perception, the miraculous slaughter of the enemy by an Angel and the withdrawal of the Assyrian forces could be attributed not only to the broad Judean acceptance of Hezekiah’s authority, but also to his personal commitment to Yahweh. Finally, the "sinful" Samaria was replaced by the "righteous" Judea; Jerusalem was saved, the promise of Isaiah was fulfilled, and Yahweh was recognized as the Only God. Considering that Kings might have had access to Berossus’ Babyloniaca, which praised Sennacherib as the most important Assyrian king, it would not be unreasonable that he chose to glorify the reign of Hezekiah by making him a counterpart of this king too. It is also possible that the author of 2 Kings might have had access to Herodotus’s History II, 141. This described Sennacherib’s unsuccessful military campaign against Egypt and reported that having reached Pelisium on the River Nile, Sennacherib suffered a disaster when field mice invaded the Assyrian camp and gnawed through the quivers, bow strings, and leather shield handles thereby disarming the military force, leading many soldiers to flee or be killed. 2 Kings altered the account given by Herodotus by transposing his story of the failure of the Assyrians in Egypt to their siege of Jerusalem, concluding that the events occurred during Hezekiah's heroic resistance to the Assyrian invasion. In fact, the conquest of Lachish by the Assyrians in 701 BC, and the siege of Jerusalem by the Persians c. 465 BC, are two different events.

While arguing that the Achaemenid period can be equated to the Neo-Assyrian one, Sweeney demonstrated a similarity between the available records of the Assyrian King Sennacherib and those of the Achaemenid King Xerxes, and proposed their identification (35, pp. 127-33). It seems more likely, however, that the confusing chronology of 2 Kings is actually the result of a literary contamination inspired by Berossus and Herodotus, rather than an identification based on fact, and that the reason 2 Kings describes the siege of Jerusalem as happening in the days of Sennacherib is the author’s apparent unfamiliarity with the figure of King Sargon. As the conquest of Samaria happened in 479 BC, and the siege of Jerusalem occurred at the end of Xerxes’s reign shortly before his assassination in 465 BC, it follows that Hezekiah’s reign can be dated to c. 480-50 BC.

The Achaemenid conquest of Judea in the fourteenth year of King Hezekiah’s reign brought an end to the hopes of liberation that the population of Judea clung to. The lengthy period of Achaemenid rule in Judea, lasting from c. 465 BC, explains the complete lack of records covering this entire period. There is no specific evidence in 2 Kings 21 relating to military activities during the reigns of either King Manasseh, the son of King Hezekiah (who is said to have reigned for fifty-five years, the longest reign in the Judean history!), or during the two-year reign of his son, King Amon; both were regarded as "idolatrous kings of Judea". Moreover, no recognizable symbols of power such as seals or bullae have been found relating, undisputedly, to either king. Despite this apparent dearth of information, there is a possibility that Judea continued to exist during this period as a semi-independent principality under the Persian protectorate. It would have been ruled from Jerusalem by a local dynasty who were regarded as being direct descendants of King David.

According to 2 Kings, during the final period of its existence the Kingdom of Judea was situated between the two super-powers of Egypt and Assyria. In the New Chronology, the "Assyrian" kings are identified with the Achaemenids, and the "Egyptians" with the rulers of the Thirtieth Dynasty. During the thirty-one year reign of King Josiah, Judea made another appeal for its liberation; this probably coincided with the formal declaration of independence from the Achaemenids announced by Pharaoh Nectanebo I (379/8-361 BC) who had survived the attack by King Artaxerxes II in 373 BC. Taking advantage of the situation, King Josiah conquered a large part of Syro-Palestine, but the situation of peaceful co-existence between the Egyptians and the Judeans dramatically deteriorated in a later period. King Josiah challenged Pharaoh Necho’s authority and when Necho "went up to [the] Euphrates to fight [the] Assyrian king", he was killed in the Battle of Megiddo (2 Kings 23:29-30). The far-reaching Egyptian military campaign mentioned in 2 Kings can be compared to the events following the death of Nectanebo I; his son, Teos, prepared an offensive against Persia that took place at the end of his brief reign, in 360 BC, when the Egyptians advanced as far as the upper streams of the Euphrates (23). Diodorus XV. 92.3-4 relates that while Teos acted in Syria, his nephew, the future Pharaoh Nectanebo II (360-40 BC) was besieging Phoenician towns; this campaign ended when Nectanebo II decided to declare himself king. The Biblical name Necho appears to be a shortened version of the name of Nectanebo II, which means that Josiah was killed by Pharaoh Nectanebo II in 360 BC. The death of Josiah brought an end to the political independence of Judea.

7. Who was Nebuchadnezzar and when was the Babylonian Exile?

The Biblical figure of King Nebuchadnezzar is not only associated with the demise of the Kingdom of Judea and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem but is also regarded as being responsible for the exile of the Jewish nation to Babylon. Scholars generally agree on identifying him with the ancient great king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Nebuchadnezzar II. However, an early 6th century BC date (around 587/6 BC) for the final destruction of Judea seems to be contradicted by available archaeological data. Archaeologists who have researched Judean settlements have found no traces of destruction in the layers dating from this period. In sharp contrast to the Biblical narrative claiming this was a time when the "land of Judah was desolated", it would appear that, on the contrary, this period saw the active expansion of different settlements located around Jerusalem. There is, however, evidence to suggest that in the middle of the 4thcentury BC not only was there mass destruction of the cities but also a significant decline in the economic situation in Judea; this was arguably caused by the mass exile of the overwhelming majority of its urban population (2). Archaeological research indicates that during the early Hellenistic period, from the mid-4th century BC and until the 370s BC, the territory of Judea was largely uninhabited, but during the later period a significant growth in the population of the country heralded a period of increased economic prosperity and a remarkable renewal of cultural and political life in Judea.

The primary sources for information concerning the final days of the Judean Kingdom are the two Biblical books: Jeremiah and 2 Kings. They record two Babylonian attacks on Judea and relate that Nebuchadnezzar replaced King Jehoiakim, the son of Josiah who was appointed king by Necho, with his son, King Jehoiachin. After reigning for only three months, the latter was sent into exile along with ten thousand skilled workers and was, in turn, replaced by his uncle, Zedekiah, whose reign lasted for eleven years. The Prophet Jeremiah was active during this period and, despite the continuing commitment of the Judean kings to Necho, he repeatedly prophesied the inevitable submission of Judea to Babylon; this led to his imprisonment. Although Jeremiah’s tendentious account is probably the more authentic one, a stylistic analysis of the Book of Jeremiah shows that it was composed by the same Deuteronomist who authored Kings (32). To confirm the positive identification of the figure of King Nebuchadnezzar, known data relating to his military activities – as recorded in accounts found in the Biblical texts – must be compared to information from external sources regarding the activities of a king who was identified by this name.

At this point we might ask if there is any additional information available in the sources that can support the Biblical story of King Nebuchadnezzar's conquest of Judea, the destruction of the Temple and the exile of the Jews. Traditionally the story of the capture of Jerusalem by the Babylonians is thought to have been independently confirmed by evidence in the cuneiform Babylonian chronicle ABC 5 that describes an attack launched by King Nebuchadnezzar II on the "Land of Hatti", during his seventh year. Interestingly, this Babylonian chronicle relates to the capture of the local king by Nebuchadnezzar and the appointment of a new king of his choice but does not report the story of the exile of the Jews. Moreover, it is not at all clear if the term "Land of Hatti" relates to the land of Judea, as this term often refers to the region of the Hattian people living in central Anatolia. Besides, the date provided by the Babylonian chronicle contradicts the statement in 2 Kings 24:12 that both the first occupation of Jerusalem and the first exile occurred in the eighth year of Nebuchadnezzar. The story in 2 Kings 24 continues in 2 Kings 25:1-7 with another siege of Jerusalem which started in the seventeenth year of Nebuchadnezzar. The second mass exile of the Jews happened soon after the fall of Jerusalem following a Babylonian siege that lasted for a period of two years, from the ninth until the eleventh year of King Zedekiah (Jeremiah 52:11; 2 Kings 24:18). 2 Kings 25:8 also relates that the Temple of Jerusalem was finally burned by General Nebuzaradan in the nineteenth year of Nebuchadnezzar’s reign. However, none of these events, which were traditionally thought to have been dated in 597-86 BC, were referred to in any Babylonian chronicles.

I believe that the events described in 2 Kings relate to a much later time, and, therefore, the figure of the Biblical King Nebuchadnezzar must be identified with the Achaemenid King Artaxerxes III Ochus (358-38 BC). The first invasion of Judea would have to be coincident with Artaxerxes III’s unsuccessful invasion of Egypt c. 350 BC while the actual events that finally brought an end to the existence of the Judean Kingdom relate to the period of 343-1 BC. The two-year siege of Jerusalem that occurred at the end of Zedekiah’s rule would correspond to the period of the successful Achaemenid offensive, led by Artaxerxes III, against the Phoenician cities, in 343-1 BC, and to his successful campaign in Egypt against Nectanebo II, which took place in 341-0 BC. Additional information about Artaxerxes III’s military campaigns are revealed in the prophesy of Ezekiel 26-28 that relates to the Babylonian conquest of Tyre and the invasion of Egypt. This suggests that the second mass exile of the Judean population occurred in 340 BC, and the destruction of the Temple would have occurred in 339 BC.

In addition to the Biblical chroniclers, these events were reflected in the Book of Judith, an early Hellenistic book that became an integral part of the Septuagint but is considered Apocrypha by the Jews (28). It portrays Nebuchadnezzar, the "King of Assyria", as a cruel conqueror of Judea and recounts the story of the resistance of the Jewish people, led by the "High Priest Joakim", against an invasion in the twelfth year of Nebuchadnezzar; this attack was commanded by Holofernes, the "Assyrian" general who was beheaded by a brave Jewish woman, Judith. The figure of Holofernes has been identified as Orophernes, the brother of the Cappadocian ruler Ariarathes, one of the satraps of Artaxerxes III. Another historical figure known from the Book of Judith is Bagoas who discovered the dead body of Holofernes; he was a eunuch of Artaxerxes III, who before playing a role in the king's assassination, had served as a general in his campaigns. If the events recounted in Judith date to the time of Artaxerxes III, this can prove that the Bible identifies Artaxerxes III as "Nebuchadnezzar", rather than identifying him as the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (35, p. 151-5). The use of the name "Nebuchadnezzar" for Artaxerxes III, the conqueror of Judea, was not accidental as this king played an important role in the Babylonian chronicles and had occupied a special position in the history of Babylon. The Babylonian cuneiform inscriptions claimed that Artaxerxes III rebuilt the city and made it his new capital (6, p. 104-5); this is, perhaps, why he would have been referred to in 2 Kings as the "King of Babylon" instead of being described, like other Achaemenid kings, as an "Assyrian".

The rebuilding of Babylon by Artaxerxes III could also explain the transfer of the thousands of Jewish artisans to Babylon since a qualified labour force would have been needed in order to execute the construction work. The Babylonian cuneiform chronicle ABC 9 reports on many prisoners taken by Artaxerxes III from the Phoenician coast to Babylon and Susa. As evidenced by many Greek and Latin authors (cf. the Byzantine author Syncellus L486.10ff.D, citing a text by Eusebius), the Jewish people were exiled twice by Artaxerxes III – to Babylon and to Hyrcania, an Achaemenid province located on the south-eastern shores of the Caspian Sea. Unlike Syncellus, who mentioned both exiles – one to Babylon and the other to Hyrcania – the Roman historian Orosius,was only familiar with the second, Hyrcanian captivity instigated by Artaxerxes III in 340 BC. Although Josephus (Ag. Ap., I, 22) retained a citation from Hecateus of Abdera, a Greek author from the late 4th century BC who related that "the Persians carried away many thousands of Jews to Babylon", he never realised that this provided crucial evidence for Persian responsibility for the exile.

8. When did Zerubbabel arrive in Jerusalem?

Ezra 1:1-11 provides further insight into the Persian perspective of ancient Jewish history and reveals the circumstances behind the return of the Jews to their land; it opens with the proclamation of the liberation of the Jews that occurred in the first year of Cyrus the Great. This information was later corroborated by a story recorded in Ezra 6:2-11 describing how, during the reign of King Darius, after Cyrus’ decree was apparently "discovered" in the archives of Ecbatana in Media, the Jews were permitted to return to their land and to rebuild their Temple. Traditionally, this decree is thought to be similar to the one recorded on the Cyrus Cylinder, now in the British Museum, which is regarded as the first "Declaration of Human Rights". The historicity of this decree, as it relates to the Jews, was questioned by Grabbe who pointed out that the Cylinder does not contain any specific reference to the Jews and that, actually, this decree could be interpreted as a general policy allowing various groups of deportees to return to their places of origin (18). The story recounted in Ezra concerning a decree that was, apparently, "found" should not be dismissed as a fantasy of its author. The story could be based on actual events that occurred in the time of King Darius when a fabricated document that was allegedly preserved from the time of Cyrus the Great, had, in fact, been produced by the Jews in Media. Such a document, when presented to the king, would have allowed the Jews to appeal for their freedom invoking the ancient king, Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid dynasty, as the supreme authority of their fate.

Following on from the story of Cyrus’s decree, Ezra 2:1-2 also relates that the first large group of Jewish exiles was led by Zerubbabel, who was sent to Judea by the Persian King Darius. With the help of the Priest Joshua, he began construction of the Temple’s altar that lasted from the second until the sixth year of King Darius’s reign (Ezra 3:1-13; 4:1-24). The texts of the Prophets, Haggai 1:1 and Zechariah 1:1, appeared to confirm this chronology; they describe that in the second year of King Darius’s reign, the Prophets Haggai and Zechariah, appealed to Zerubbabel and Joshua concerning the building of the Second Temple. In order to precisely date the commencement of the process to rebuild the Temple, as well as to establish the circumstances that led to the Jews’ return from exile, it is necessary to determine the dates of King Darius's reign. One possibility to be seriously considered is to identify King Darius as the last Achaemenid king, Darius III (336-30 BC). In this case, the return of the first group of Jews would have occurred in 335 BC, and the process of rebuilding the sacrificial altar could, therefore, be dated to c. 335-30 BC.

The possible identification of the figure of King Darius in Ezra with the mysterious figure of King Darius the Mede in Daniel raises questions about the actual historical circumstances surrounding the early release of the Jews from their Babylonian captivity, prophesied by Daniel. Traditionally, it was assumed that Prophet Daniel was a child when he was taken into exile by Nebuchadnezzar II, and that he lived in Babylon in the 6th century BC until his death at the very end of the Babylonian Empire, c. 539 BC. In the course of research it has become clear, however, that the entire story of Daniel was set in the Hellenistic period since the main body of Daniel was composed during the 4th century BC although there were, clearly, some later additions as his prophecies related to the events of a future period. It has, therefore, been proposed that there were two figures called Daniel – one living in the 6th century BC and the other living in the 4th century BC – and that they were combined by a later, 2nd century BC editor of Daniel. What if, however, all the chapters relating to the adventures of Daniel and his role in the life of the Babylonian captives are from the 4th century BC? Is there a possibility that Daniel was a 4th-century BC historical figure?

The story of the Book of Daniel contains an account of an episode, when Daniel, while attending a banquet given by King Belshazzar, the son of Nebuchadnezzar, was invited to read a strange inscription that appeared on the wall. Based on his interpretation of it, Daniel 5:28 prophesied the imminent overthrow of King Belshazzar and the conquest of his kingdom following an invasion by Medes and Persians. Daniel 6:30-31 also reports that the prophecy was, indeed, fulfilled: King Belshazzar was killed, and Babylon was conquered by King Darius the Mede. This king held Daniel in high esteem and rewarded him with important positions, including that of the Chief Governor of Babylon, which led to a conspiracy against him. Following Daniel’s miraculous escape from the lion's den, King Darius, filled with awe at what had happened, issued a decree that everyone should worship "The God of Daniel" (Daniel 6:26). If the historicity of the events described in the Book of Daniel can be proven, it may be argued that the Jewish-oriented policies of Darius the Mede might have been due to the influence that Daniel exerted over him. When previous generations of scholars were attempting to set the story of Daniel into the historical reality of the 6th century BC, they noticed that, according to all the available historical sources, the Babylonian Empire was conquered in 539 BC by the Achaemenid King Cyrus the Great, and furthermore that the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire was named Nabonides, not Belshazzar. These comments raised doubts about the historicity of Belshazzar and Darius.

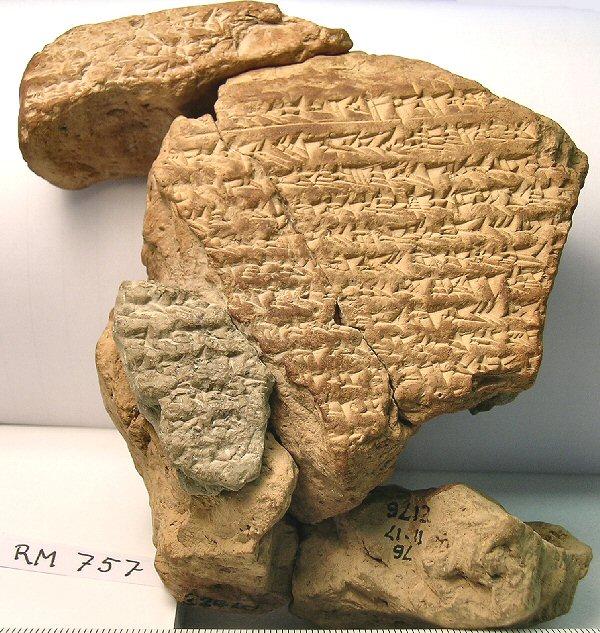

Coin of Artaxerxes V Arses

In my opinion, the historical reality behind the chapters of Daniel telling of the invasion of Babylon by the Median and Persians forces fits better into the turbulent political situation pertaining in Babylon after the death of Arses (338-36 BC) – Artaxerxes IV – the son of Artaxerxes III Ochus, who could have been identified by Daniel as King Belshazzar, the son of King Nebuchadnezzar. It should be noted that Darius the Mede was named the son of Ahasueros in Daniel 9:1, allowing him to be equated with the Persian King Darius III; he was a governor of Media and rose to power following the assassination of Arses by Bagoas, the same general who poisoned Artaxerxes III. The Greek sources agreed that Darius III was not a member of the mainstream Achaemenid dynasty, which is why Alexander the Great was able to justify his military actions against him, believing that he was actually restoring order by removing an imposter from the throne. This suggests that when the Median and Persian forces took control of Babylon in 336 BC, Darius III, who previously ruled Media, was declared the King of Persia, and Daniel was then appointed as the supreme ruler of Babylon. It can be inferred that Darius III took his important decision relating to the fate of the Jews as a result to the influence exerted by Daniel, and that, following the conquest of Babylon by the Persians and Medes forces, the prevailing situation enabled Zerubbabel to leave in the following year. Thus, the information revealed in the Book of Daniel could explain the unexpectedly positive attitude of the new ruler towards his Jewish subjects, as well as the circumstances behind their miraculous escape from captivity.

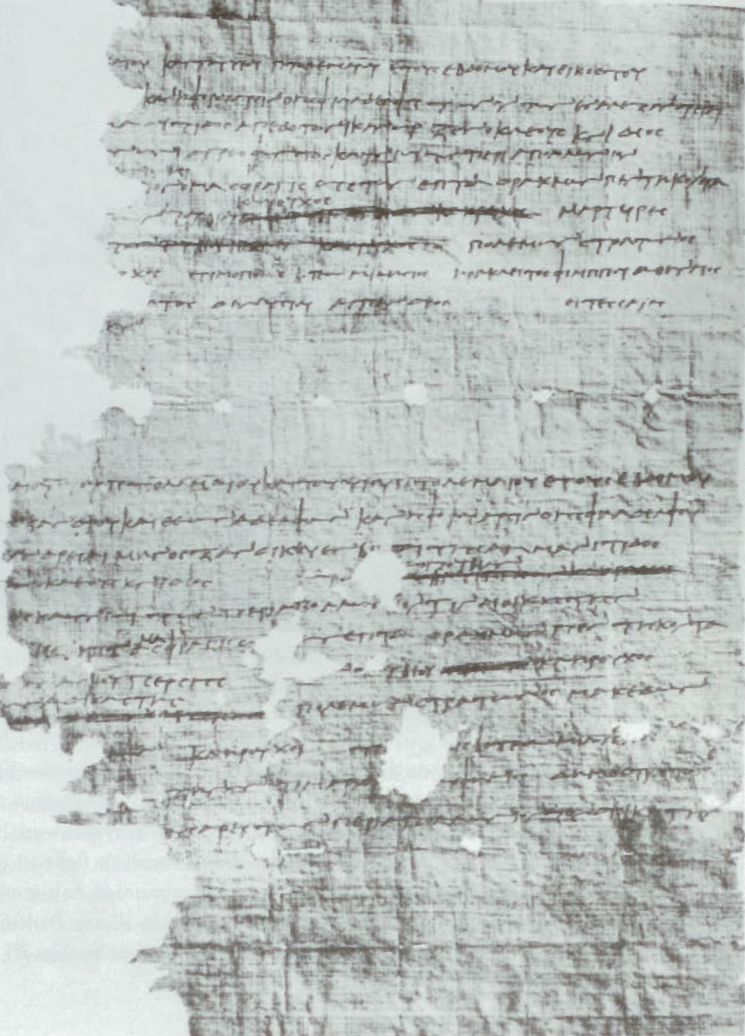

The pro-Jewish attitude of King Darius is revealed in a letter written in Aramaic from the collection of the Elephantine Papyri found in Lower Egypt, often referred to as the Passover Papyrus (30: B13); this document has been previously dated by scholars to 419 BC. In the letter, dating from the fifth year of Darius, an official named Hananiah informed an officer named Yedaniah about the strict regulations for Passover observance that had been approved by Darius for the Jewish soldiers who were entrusted to protect Persian interests and garrisoned in Elephantine. The name of Hananiah pehah also appears among Samaritan Wadi Daliye Papyri dated after the Macedonian invasion (10), as well as on a bulla found in the post-exile archive that presents him as an officer in charge of fiscal matters (1). The fact that a Persian king took an interest in Jewish religious matters indicates the special feelings this king had towards his Jewish subjects. Thus, the reference to Darius III in the Passover Papyrus, written in 331 BC, points to his ultimate authority over Lower Egypt and can be regarded as additional confirmation that this region remained under Persian rule.

Proof of the power exerted by the Persians over Judea is revealed in another document of the Elephantine Papyri, referred to as the Petition to Bagoas (Bagavahya), Governor of Judea, and dated from the seventeenth year of King Darius (30: B19; B20). The Petition was written to the Persian governor and requested help in rebuilding the Temple in Elephantine that had been demolished by the Egyptians; it was composed by Jewish soldiers led by Yedaniah, who were guarding Persian interests in the Lower Egypt region. The Petition related that the High Priest of Jerusalem, Johanan, had denied a previous request, and it also mentioned that another petition had previously being made to Delaiah and Shelemiah, the sons of Sanballat. This name appears to be identical to that of Sanballat, the Samaritan governor who according to Josephus XI:7,2 was appointed by Darius III. It confirms that, long after Darius III's death, the Jewish population of Lower Egypt continued to count the dates according to his reign, while appealing to Bagoas, the governor of Judea, as a supreme authority.

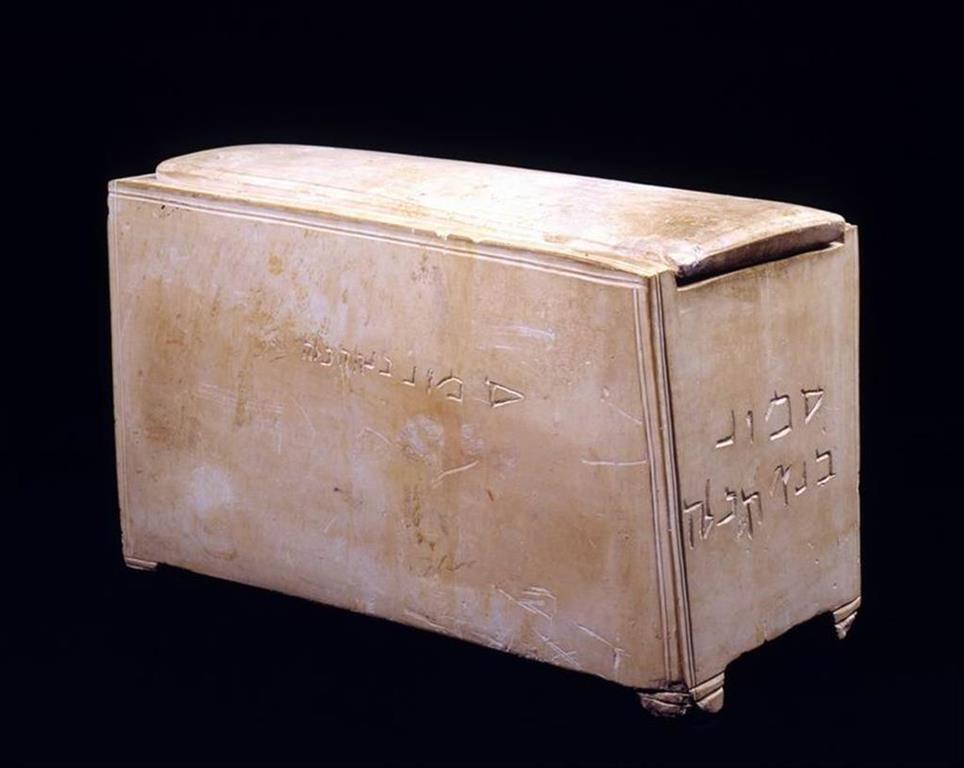

The British Museum

Bagoas coin

Josephus XII:7,1 recounted a story of how Bagoses, a Persian strategos of Artaxerxes III, interfered in the appointment of the Jewish High Priest by supporting Joshua, a candidate who was ultimately killed by his brother Johanan in a fight for the office. To show his anger at Joshua’s murder, Bagoses desecrated the Temple by walking into its inner court and persecuted the Jews by imposing heavy taxes. However, it seems that he allowed Johanan to continue serving as the High Priest. There is every reason to believe that the source of Josephus’s story related to the death of Joshua, Zerubbabel’s companion, and dated to the time of King Darius III. General Bagoses is, in fact, not only identical to the eunuch of Artaxerxes III but also to Bagoas (Bagavahya), who was regarded as the primary authority in Judea and was the actual addressee of the Elephantine Petition. Bagoses/Bagoas, who was one of the heroes in the Book of Judith, participated in the Achaemenid conquest of Judea in 341 BC and played a decisive role in the assassinations of Artaxerxes III and his son Arses in 338 BC and 336 BC, respectively. He was also involved in the appointment of King Darius III and was regarded as the chief supervisor of the region of Judea on behalf of King Darius III. Bagoses’s portrait appears on a unique silver drachm from the British Museum collection, where he is shown wearing a helmet on the obverse, with the image of Yahweh enthroned and sitting on a winged wheel, on the reverse (33). This unusual and unique anthropomorphic representation of the Jewish God, Yahweh, next to the figure of a Persian general confirms the enormous respect the Persian authorities felt for the Jewish religion during the days of Darius III.

9. When did Nehemiah arrive in Jerusalem?

The Biblical narrative suggest that the fate of the Jewish nation started to improve when the Persian King Artaxerxes sent his "cupbearer", Nehemiah, a Jew from Susa, to govern Judea; he was accompanied on this mission by a group of local Jews. His deeds are described in Nehemiah'sMemoirs, which were later incorporated into the Book of Nehemiah; the Memoirs are written in the first person and are believed to have been composed by Nehemiah himself, thus providing an authentic and reliable source of information. The thoughtful textual analysis offered by Jacob Wright supports the idea of the "process" of a gradual evolvement, in three major redactions, of the Book of Nehemiah that all took place during the Hellenistic period (39). In his opinion, it was developed from an original text covering the encounters between Nehemiah and Artaxerxes, a brief report on the wall-building, and another polemic text, written by Nehemiah against his enemies. Nehemiah relates that he served under Artaxerxes from his twentieth year (2:1; 13:6), after which he was recalled to the king's court although he did return to Jerusalem in his thirty-second year. Nehemiah claimed that, upon his initial arrival, he found Jerusalem in ruins and lacking any form of administration; therefore, he decided that his primary objective would be to rebuild the destroyed walls of the city. He recorded that he was initially supported in the execution of this project by the High Priest Elyashiv (3:1). This project did not meet with unanimous approval and there are frequent references to Nehemiah’s influential adversaries who strongly objected to it. These people were all local leaders: Geshem, the Arab; Sanballat from Horon; and Tobiah of Ammon. The key questions to be answered are: firstly, when did these people live; and secondly, which Persian king sent Nehemiah on his mission?

Traditionally, scholars assumed that the events recorded in Ezra-Nehemiah must be dated to the Achaemenid period. In view of the weak archaeological data attesting to Jerusalem as an urban centre during the Achaemenid period, Israel Finkelstein doubted that the small population of Jerusalem, estimated to be around five hundred people, could have produced anything of literary significance. Accordingly, he proposed a radical re-evaluation of the research by suggesting the Hellenistic period as the setting for the historical events and figures that are mentioned in Ezra-Nehemiah. In support of a Hellenistic date for these texts, he cites a number of examples: for instance, some of the Judean cities that the builders of Nehemiah's wall came from did not exist in the Achaemenid period and were only built in Hellenistic times; moreover, there is no evidence of city walls built in Jerusalem between the Iron Age and the Hellenistic period (13, p. 3-27; 71-82; 102-6).

While Finkelstein maintains that the historical realities of Judea as they are described in Nehemiah could only have existed in the Hellenistic period, and preferred 2nd century BC over the 3rd century BC as a historical setting, he did not, however, address the question of the actual dates of Nehemiah’s mission. Dating Nehemiah’s activities to the 5th century BC and his book to the 2nd century BC prevents it from being regarded as a reliable record of historical events. However, what if Nehemiah – as well as his adversaries – were real historical figures of the Hellenistic period whose deeds were described in the Memoirs, while the Book of Nehemiah was reedited in a later period?

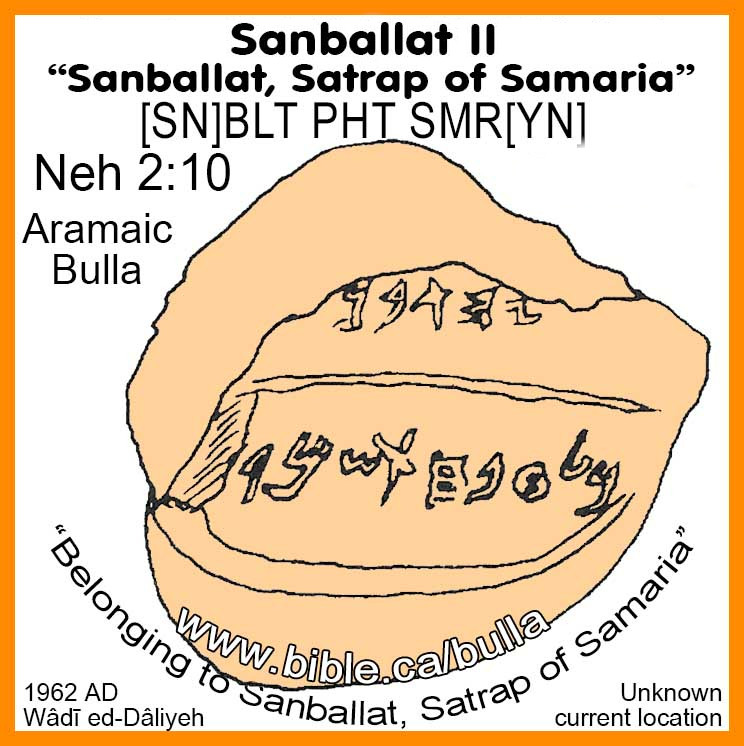

As Finkelstein pointed out that the names of Nehemiah’s adversaries only appeared in original documents from the Hellenistic period, we must look for the correct timeframe when all these figures could have acted together. The figure of Sanballat from Horon, mentioned in Nehemiah, is identical to the governor Sanballat of Samaria, who was described by Josephus XI:7, 2 as the first governor of Samaria serving on behalf of King Darius III. Different coins bearing this name have been discovered (26, pp. 26-27), and his name has also been found on a bulla of his son, Yeshayahu, that was excavated alongside the Wadi Daliye Papyri, a collection of Samaritan legal documents, written in Aramaic, which were dated by the scholars to the mid-4th century BC (10). Interestingly, some of the Papyri were dated according to the reign of King Artaxerxes; in others, the presence of Greek soldiers in Samaria is mentioned. Since the name of the Persian king who reigned during the Macedonian conquest was Darius, not Artaxerxes, and the Greeks were known to have conquered Samaria first under Ptolemy I in 312 BC, it can be suggested that these Papyri belonged to the time of fratarakā Artaxerxes and must therefore be dated between 321 - 12 BC.

Amongst Nehemiah's adversaries, the figure of Tobiah, the Jewish ruler of Ammon, is the most puzzling. Nehemiah 4:1-8 stated that Tobiah was initially very close to Sanballat and supported him in his resistance to Nehemiah’s project of rebuilding the walls around the city of Jerusalem. Nehemiah 13:7-9 also relates that, upon Nehemiah’s return to Jerusalem after visiting King Artaxerxes, he found that Elyashiv had become friendly with Tobiah and had given him a separate chamber in the Temple in which to keep his precious possessions. This angered Nehemiah who reacted by throwing out his belongings and then ordering the chamber to be cleansed. Using information from an early Hellenistic source, the Tobiades Roman, Josephus XII:4 recounted the story of the rise to power of the aristocratic family of the Tobiades and stated that Tobias (a Greek version of the name Tobiah) was the founder of the Jewish dynasty of the rulers of Amman. The Tobiades Roman includes an account of Joseph, the son of Tobias, who had a successful career under the Ptolemies; he rose to prominence after the High Priest Onias had stubbornly refused to pay the taxes demanded by Ptolemy, and Joseph was appointed to be the tax collector for the Syro-Palestine region. Josephus dates these events to the time of Ptolemy V Epiphanes, after the region was returned to him by Antiochus III as part of the dowry for the marriage of his daughter Cleopatra I to Ptolemy V in 193 BC. According to Grabbe, although the general dating of the events in Josephus does not make sense, Josephus’s mistakes in placing his sources into an overall framework do not detract from the fact that the whole story is original (19, p. 136-139). What, however, was the historical setting for the story of the rise to power of the Tobiades dynasty?

It seems that the most probable timeframe is that of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283-246 BC). This can be confirmed by a collection of documents found in the archive of Zenon Papyri discovered in Philadelphia, in Egypt. Zenon was an agent of Apollonius, the finance minister of Ptolemy II, and in 259 BC he was sent to Syro-Palestine to establish trading contacts. Upon his return, he continued to maintain a connection with his partners there and communicated several times with Apollonius on different matters. A number of documents connected with Zenon’s tour found their way into his archives, including a bill of sale for a slave from year 27 of Ptolemy II (256 BC) that briefly mentioned Tobias, and a personal letter of Tobias from year 29 of Ptolemy II (254 BC) that records his gift of slaves to Apollonius. In the former document Tobias is noted as overseeing the birta, a fortress located in the Ammonite region. This information may confirm that Tobias, who had occupied a prominent position under Persians, retained his power when the region came under Ptolemaic rule. In addition, another letter from the Zenon archive, dated from year 27 of Ptolemy II (256 BC), mentions a Jewish leader named Jeddous (Jaddua). The same person, who served as a High Priest, is also known to Nehemiah 12:11 as a younger member of the family of Elyashiv.

Josephus XII: 4, 11 also recounts that later, during the reign of Seleucus IV (187-175 BC), the youngest son of Joseph, named Hyrcanus, proclaimed himself an independent ruler of an area surrounding the fortress of Tyros in Transjordan; he controlled this region for a period of seven years, fighting local tribes of Arabic origin, before finally committing suicide. Hyrcanus's splendid fortress in Tyros, described in detail by Josephus, has been identified as the Hellenistic castle of Qasr al-Abd, in Araq el-Emir, whose ruins stand in the valley of Wadi as-Seer, to the west of Amman.

As the Memoirs of Nehemiah reported that Nehemiah was sent on his mission by the Persian King Artaxerxes, to clarify the timeframe for Nehemiah, it is important to establish his identity and the dates of his reign. Traditionally, it is claimed that Judea remained under Persian rule until the Macedonian conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in 332 BC, and that in the Hellenistic period, following the fight of the Diadochi, it lay between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid Empires; the Ptolemaic rule is generally accepted as having lasted from 302/1 BC until Antiochus III’ conquest in 200 BC following which control of Judea passed to the Seleucids. Historians generally believe that the Achaemenid Kingdom ceased to exist as a strong political entity after the Macedonian conquest and, therefore, rejected the possibility that Persian rule in Judea could have continued after 332 BC. However, in the light of recent research on the history of the Kingdom of Persis, this concept now needs to be reviewed. The concept of the political revival of Persia during the early Hellenistic period promoted by scholars is mainly supported by numismatic evidence (6; 7; 8; 16; 28).

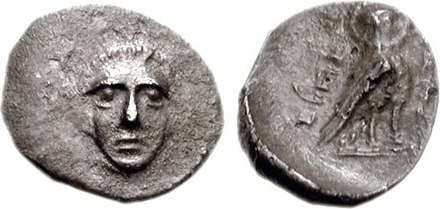

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Coin of Artaxerxes frataraka

The relative chronology of the fratarakā kings of Persis is disputable and, due to the fragmentary nature of the written sources, research is primarily based upon the evidence of the locally-minted silver coins on which the fratarakā rulers expressed their close ties to the Achaemenid kings. It was initially proposed that this Hellenistic dynasty emerged in Fars as Seleucid representatives, and that the Kingdom of Persis was released from Seleucid rule around 275 BC. Furthermore, it was previously thought that fratarakā Bagadad was the first independent ruler of Persis and that he initially overstruck Seleucid coins before later minting coins with his own name, apparently written in Aramaic script. He is depicted wearing a satrap headdress and Hellenistic diadem and either making devotions to a fire altar, or enthroned (21). The reign of Bagadad was believed to be followed by other fratarakā rulers, named Vahbarz, Vadfradad, and Artaxerxes. More recently, however, this sequence of fratarakā was challenged, and it was suggested that the first independent ruler of the Hellenistic Kingdom of Persis, following Macedonian invasion, was named Artaxerxes (16; 28). The issue of the silver drachm coins of the fratarakā, Artxashastra (Artaxerxes), found in a hoard in 1986 next to coins of Seleucus I (312-281 BC) and published by Brian Kritt in 1997, record a crucial moment in the Hellenistic Kingdom of Persis securing its independence (7). The obverse of these coins depicts a bust wearing a satrap hat, and on the reverse, he is shown standing with raised hands in front of a ritual square structure, which is often identified by scholars as the fire altar of the Zoroastrian Temple.

The important question that remains unanswered is: how should the beginning of fratarakā Artaxerxes’ reign be calculated? In my opinion, all the Elephantine Papyri that belong to the period of King Artaxerxes’ reign, and thought to date to the 5th century BC, actually, can be related to fratarakā Artaxerxes. The group of Papyri dated from the 6th until the 19th year of Artaxerxes’ reign belonged to Mahseiah, the son of Yedaniah, who served under Darius (B25-B29); this suggests that Artaxerxes reigned after Darius, not vice versa. In addition, the first mention of the term fratarakā found in the Elephantine Papyri dates from the period of Artaxerxes; no such title was recorded in the Achaemenid period. The latest documents of the Elephantine Papyri that were issued during the time of King Artaxerxes are dated to the thirty-eighth year of his reign (B10; B37; B39), indicating that the Persians maintained control of Lower Egypt after the Macedonian invasion. On the other hand, the earliest Papyri, which date from the time of Ptolemy I (304-282 BC), survived from his 40th year (D3), meaning that this region passed to Ptolemaic control in 284 BC. These dates suggest that the reign of fratarakā Artaxerxes started in 322 BC, soon after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. It, therefore, follows that Nehemiah’s appointment in the 20th year of King Artaxerxes occurred in 302 BC. The consequences of Ptolemy I’s disastrous attack on Jerusalem that occurred in the same year would explain why, when he arrived in Jerusalem, Nehemiah found a scene of destruction and a city without administration.

It can be suggested that following Seleucid conquest of Babylon in 312 BC, the Persians and the Greeks managed to co-exist peacefully. However, comparative analysis of the sequence of hoards preserved with the victorious coins of King Seleucus I minted in Susa in 301 BC, with the stratigraphic observations on the destruction level in Pasargadae that was burned to the ground c. 300 BC, suggests that, when fratarakā Artaxerxes challenged Seleucus I in 302/1 BC, this led to a large-scale confrontation. Considering that he first rose to power in 322 BC, it can be inferred that it was twenty years later that fratarakā Artaxerxes not only exerted his authority over the lands of Fars but also attempted to reclaim previously held Achaemenid lands. Accepting that the Persian King Artaxerxes V referred to by Nehemiah was none other than fratarakā Artaxerxes, and that Nehemiah ruled as pehah - Governor of Judea - from his 20th until his 32nd year, the general timeframe of Nehemiah’s rule can be established within the period of 302 - 290 BC, although it seems possible that upon his return to Jerusalem following his visit to the King, he might he might have continued being in charge during the later period, until around 275 BC.

It is significant that Nehemiah’s Memoirs begin with the period when he served in the king’s castle in Susa. The excavations of that city reveal, at the southern point of the mound of the Royal Town, the Donjon, a monumental government building from the Hellenistic period that could have served as the king’s castle (38). Before the attack of Seleucus I in 301 BC, the capital of the kings of Persis was in Susa, although it later moved to Persepolis, the old ceremonial seat of the Achaemenid kings. Apparently, the city of Susa was also the capital of Ahasueros who appears as a central figure in the events of Purim described in the Book of Esther. As Ahasueros is the Aramaic version of name Artaxerxes, this identifies the fratarakā Artaxerxes as the hero of the Purim story. While scholars rejected the historicity of this book, based on Hellenistic details in the depictions of the king’s court and, pointing to its unfamiliarity prior to the 3rd century BC, they have assumed a Hellenistic date of the book that seems to describe events that allegedly took place in the Achaemenid period. In my opinion, it appears to, actually, be an authentic and contemporary – although very biased – description of events that took place in the early Hellenistic period.

It is not an accident that Nehemiah was portrayed, not as a figure from the remote past, but as the predecessor of Judah the Maccabee in an event recounted in a letter sent by Jews in Jerusalem to their coreligionists in Alexandria in 188 S. E. (124 BC) and preserved in 2 Macc. 1:20-36 (37). This letter described how, during the purification of the sacrificial altar in Jerusalem at the Holiday of Sukkot, the altar was miraculously restored by Nehemiah, who used a substance called nephthar ("oil") to kindle the sacred fire hidden by priests of the Temple before they went into exile. Theodor Bergren has argued that this narrative seeks to demonstrate that there was continuity between the First and the Second Temples cults, and that there was a historical precedent for Judah the Maccabee’s purification of the sanctuary (2), nevertheless certain details of this narrative, which remained unknown to Nehemiah, suggest that is should be regarded as an authentic account. During the purification of the altar, Nehemiah was aided by the Priest Jonathan, who was identified by Nehemiah 12:11 as the son of Joiada, and the grandson of Elyashiv. Interestingly, although this narrative only focuses on the restoration of the altar, not on the Temple itself, this information can also be compared with 2 Macc. 1:18, where Nehemiah was credited with constructing the walls of Jerusalem as well as with the building of the Temple. In addition, 2 Macc. 2:13-15 also credited Nehemiah with gathering the Hebrew books; taken together, these provide us with additional arguments in favour of Nehemiah’s exclusive role in the formation of the Biblical canon.

From: Die Bibel in Bildern

Judah the Maccabee commanding rededication of the Temple

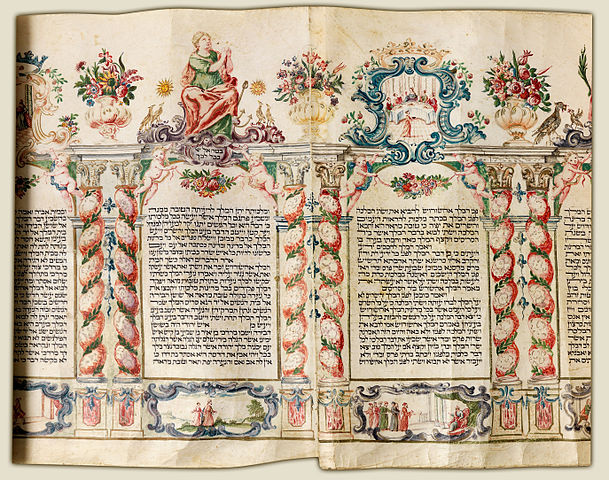

10. When was the Hebrew Bible composed?

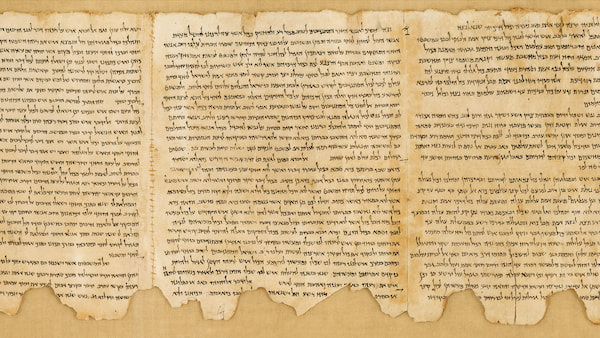

Resolving the question of the origin, authorship, and dating of the Five Books of the Torah, the most important books of the Hebrew Bible, is one of the key issues for establishing the historical value of the Bible. Recently, the traditional view regarding the dating of the Pentateuch as well as circumstances of its composition, was challenged by Russell Gmirkin. In his opinion, the main redaction of the Hebrew Torah was issued shortly before its Greek translation, the Septuagint, which was composed by seventy Jewish sages in Alexandria under Ptolemy II c. 270 BC; this indicates that the editors of the Hebrew Torah could indeed have utilized the books of the early Hellenistic historians – Manetho, who wrote in Ptolemaic Egypt, and Berossus, who was active in Seleucid Babylon – as evidenced by the literary dependence of the Torah on their texts, issued around 280-78 BC (16). Later, Gmirkin also argued that the laws of the Torah were influenced by the ideas of Plato’s Laws housed in the Great Library of Alexandria(16a).