1. Introduction

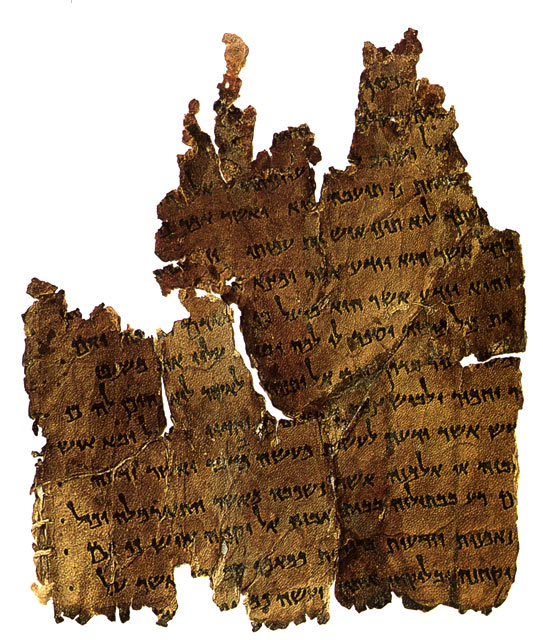

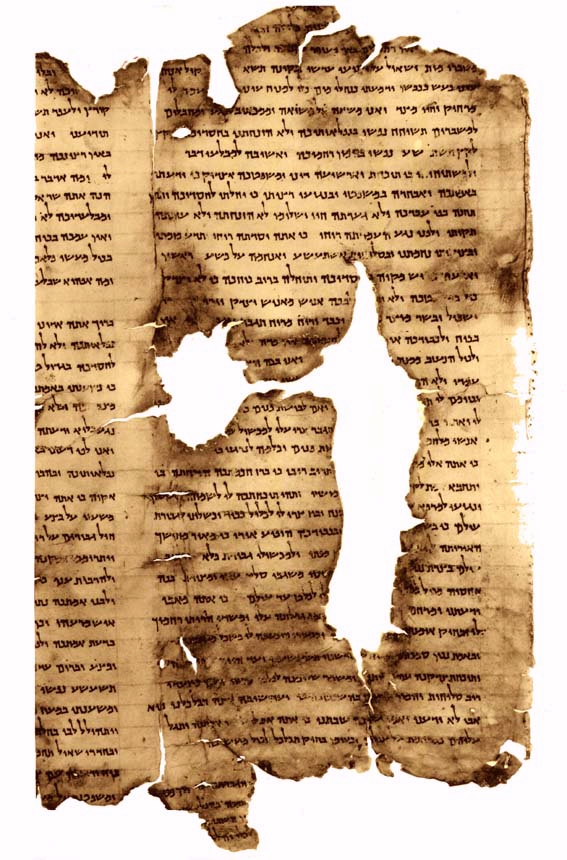

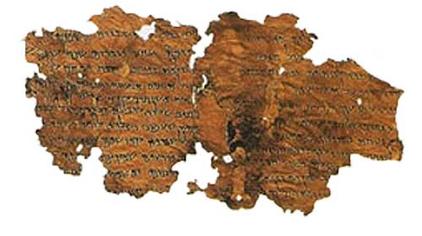

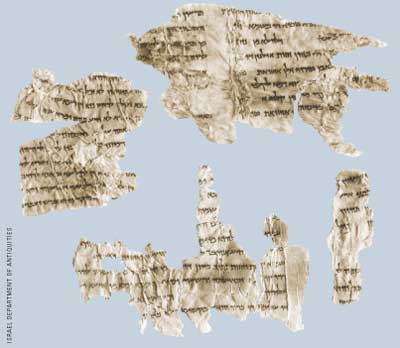

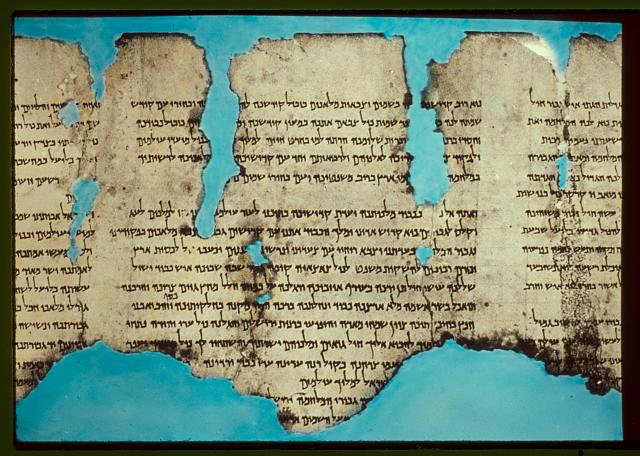

At the end of the 1940s and beginning of the 1950s, many ancient scrolls and parchment fragments were discovered in caves near the oasis of Qumran on the north-western shores of the Dead Sea. The authorship of these documents remains an unsolved mystery until this day, as does their chronology. This remarkable collection of documents includes not only the earliest known Biblical manuscripts written in Hebrew, but also many original and unique texts in Hebrew and Aramaic that are assumed to have been composed by the Jews who had hidden the Scrolls in the Caves of Qumran. In order to properly establish their historical value, and to determine when they were written and by whom, it is crucial to research the historical framework and the distinctive terminology that was used in these texts.

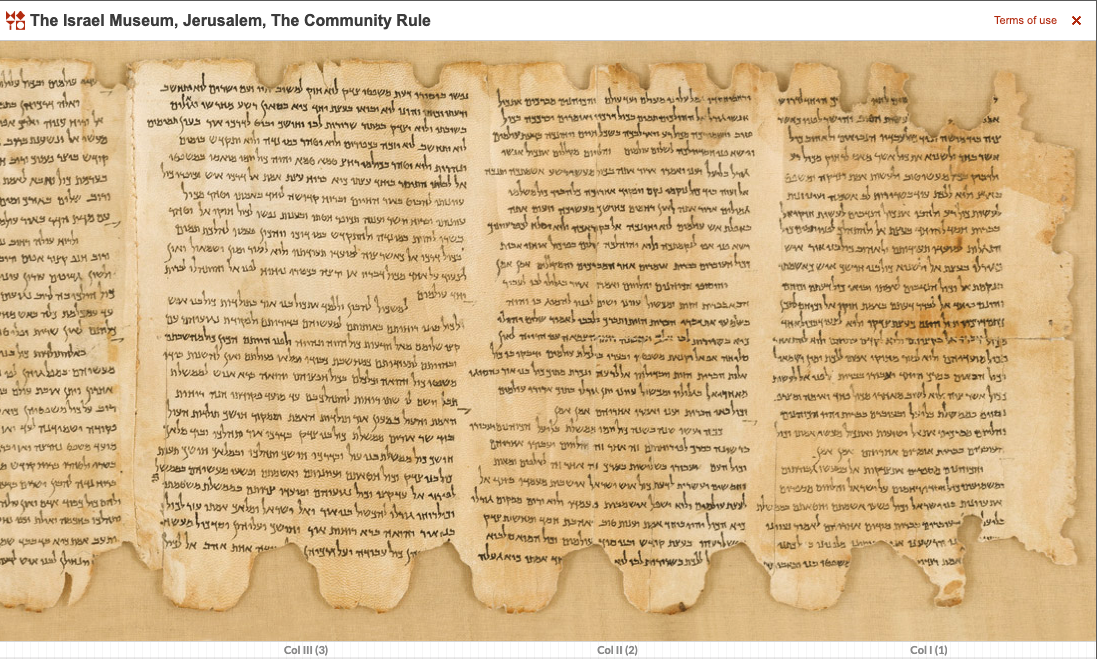

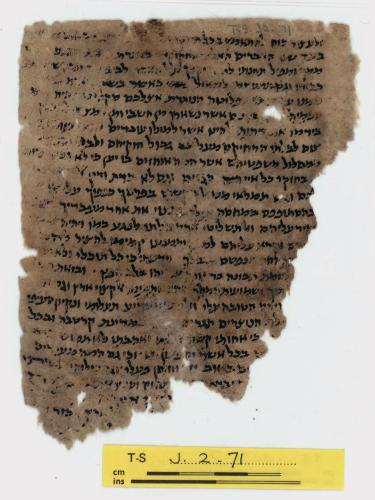

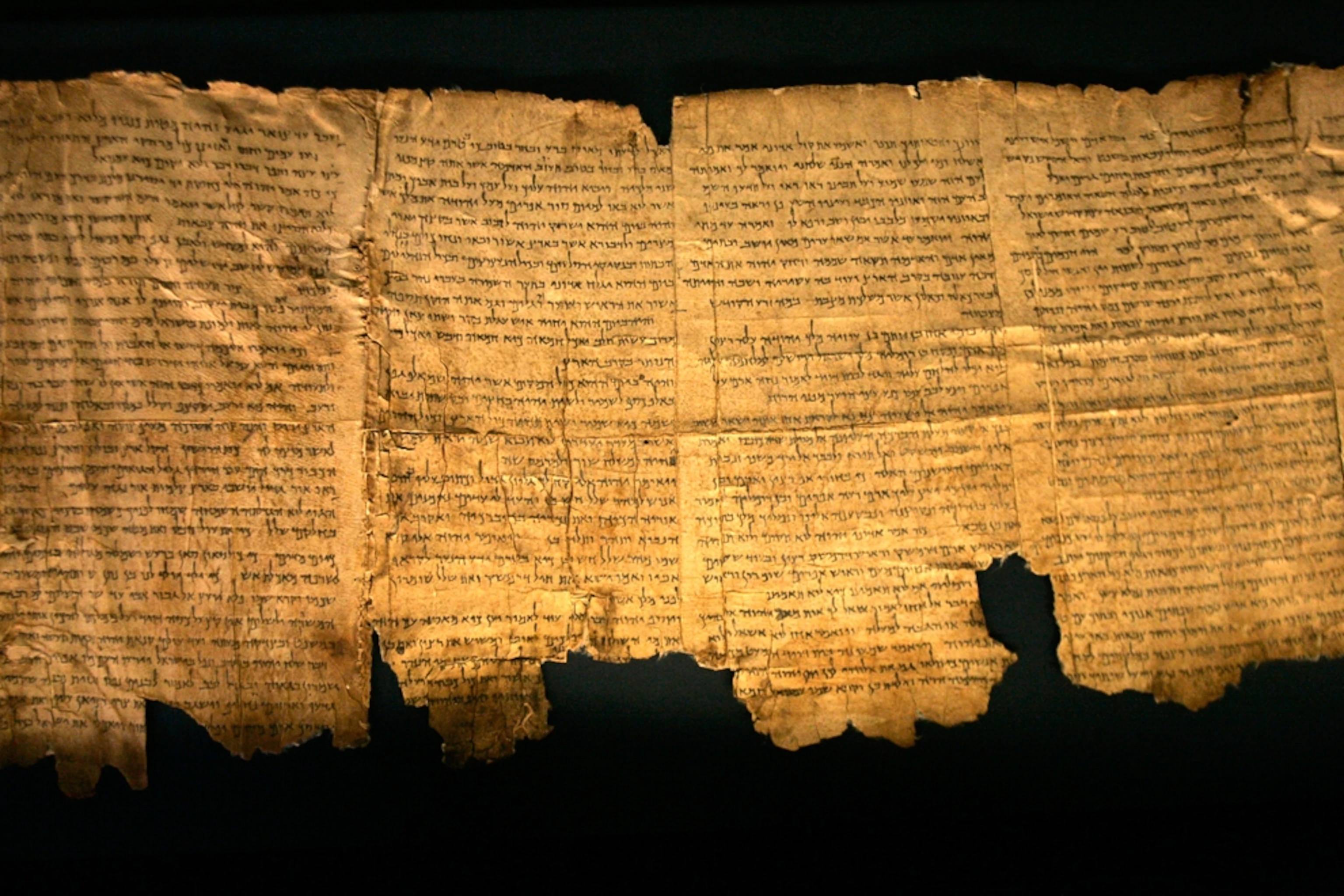

Israel Musesum. Photograph by Baz Ratner, Reuters

Dead Sea Scrolls

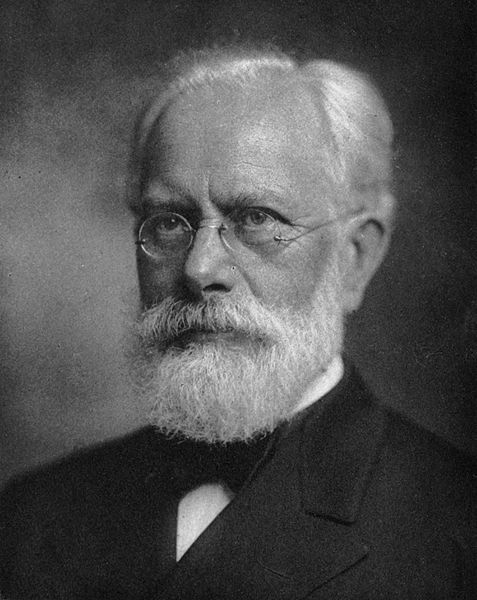

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

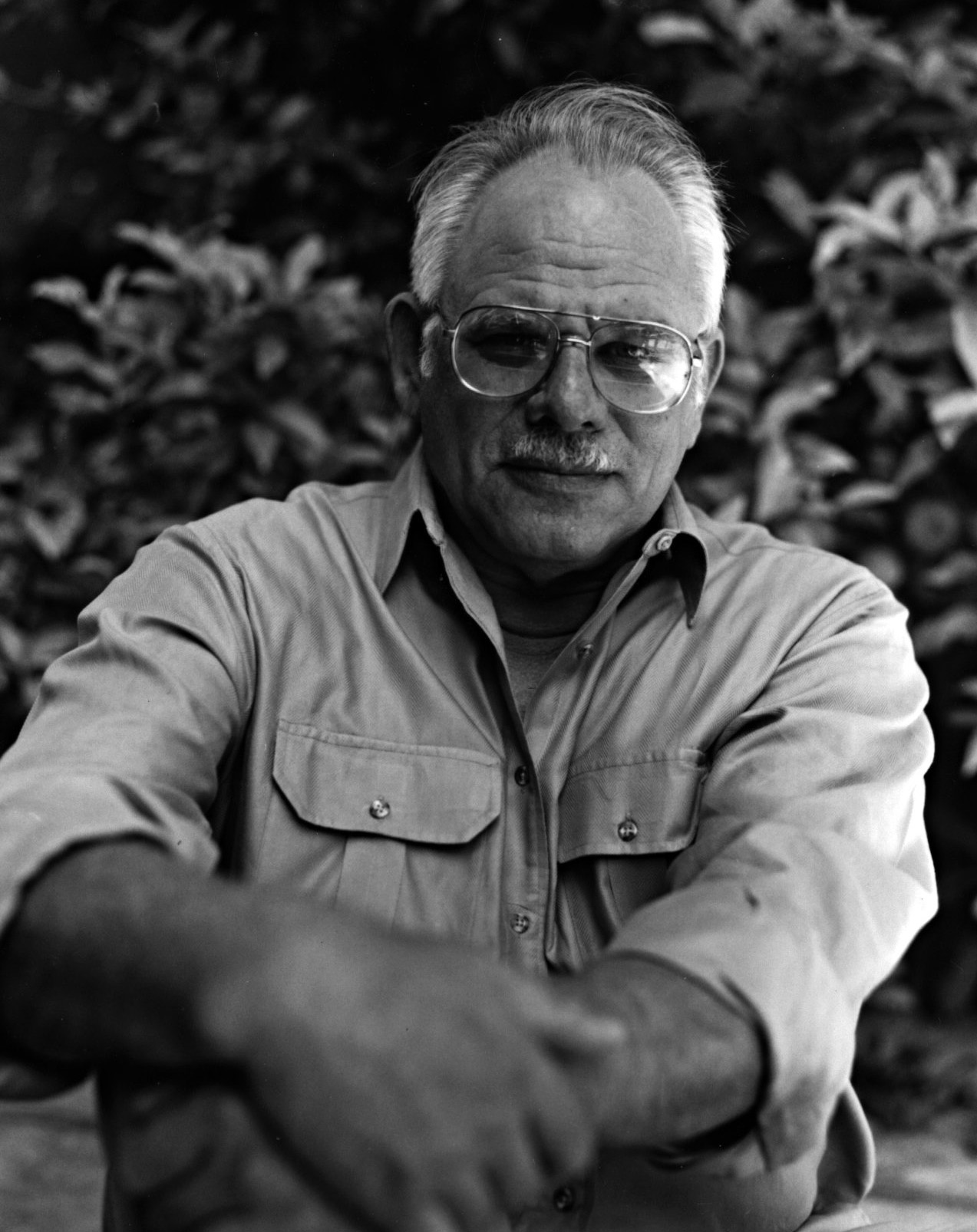

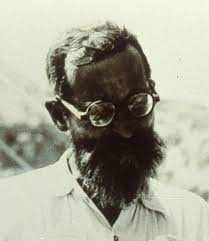

Roland de Vaux

The Dead Sea Scrolls were first examined in the early 1950s by a team of Dominican monks led by Father Roland de Vaux; they reached the conclusion that they had been written by the Essenes, a small group of Jewish sectarians, who according to Josephus Flavius and Pliny, settled in the area close to the Dead Sea in the 1st century BCE - 1st century CE, where they lived frugal and celibate lives. This would suggest that most of the Scrolls were composed during the Maccabean period, meaning that they were of pre-Christian origin and thus irrelevant to the story of Jesus, the Christian Messiah. At the time, this assessment gained wide acceptance, not only amongst Israeli scholars, but also within the wider academic world4. The Scrolls, therefore, continued to be viewed for a long time as authored by a small group of anti-establishment ascetics who had deliberately chosen to live in quiet seclusion in Qumran, far from the hostile priesthood of Jerusalem. Following their eventual publication, the Dead Sea Scrolls were re-evaluated and there was no longer a consensus with regard to their authorship. It was accepted that the halakhic ideas expressed in the Scrolls, especially in the Halakhic Letter81, did not fully match the views previously attributed to the Essenes, especially in respect of their idea of celibacy128. These rules were comparable, however, to those found in the Talmudic sources that the rabbis attributed to their adversaries, the sectarian Jews known as the Zadokim, who were regarded as descendants of the Sadducees - the enemies of the Pharisees, the spiritual ancestors of the rabbis. It should also be stressed that there is not a single mention of the Essenes in the Scrolls; instead, it appears that the sectarians regarded themselves as descended from the tribe of “Judah”, and their leaders the “Sons of Zadok, the priests”.

Lawrence Schiffman pointed towards a later self-identification of the sectarians and decided that the “Zadokite” identity, in fact, reflected their Sadducean origin. After examining the approach towards Halakha in the Scrolls – particularly with respect to the rules relating to matters of ritual purity – with the rules set out in the Talmud and ascribed to the Zadokim, he concluded that the Scrolls were composed by an “extreme branch” of Sadducean Jews. He identified them as the small group of aristocratic priests who had been in charge of the Second Temple; following the installment of the Maccabean High Priest in place of the Sadducean one, they had fled from Jerusalem to Khirbet Qumran and settled there on the eve of the Maccabean Revolt, around 152 BCE129. The problem with this approach, however, is that there is no evidence that the Sadduceans ever occupied the position of High Priest prior to 152 BCE. Additionally, there is no mention in any sources, including Josephus Flavius, of the Sadduceans existence prior to the time of John Hyrcanus (134-104 BCE). During the later period, however, and up until the hurban – the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 CE, the Sadducean priests were responsible for maintaining the Temple services, and would have had no reason to leave Jerusalem, or to oppose the Temple’s cult.

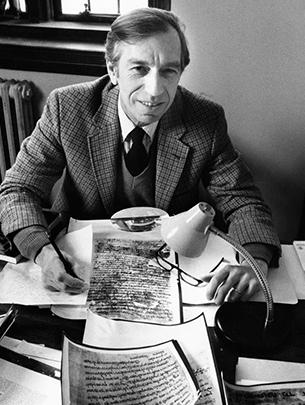

While Norman Golb agreed with the “Sadducean” identity of the sectarians, he argued against the connection between the Caves of Qumran and Khirbet Qumran. The disparity in approach found in the Scrolls led him to conclude that they had originated in a number of different libraries in Jerusalem and had been removed and hidden in the Caves of Qumran after 70 CE. His analysis of the sectarian writings of Qumran, in particular, the Pesharim – the original commentaries that contemporized Biblical Prophetic events – suggests that these texts reflect the diversity amongst different rival groups during the time of the First Jewish Revolt51. In my opinion, and as will be shown below, Golb’s claim that the Scrolls were hidden soon after the hurban does not take into account that some of the events referred to in the Pesharim must be dated to the time of the Second Revolt.

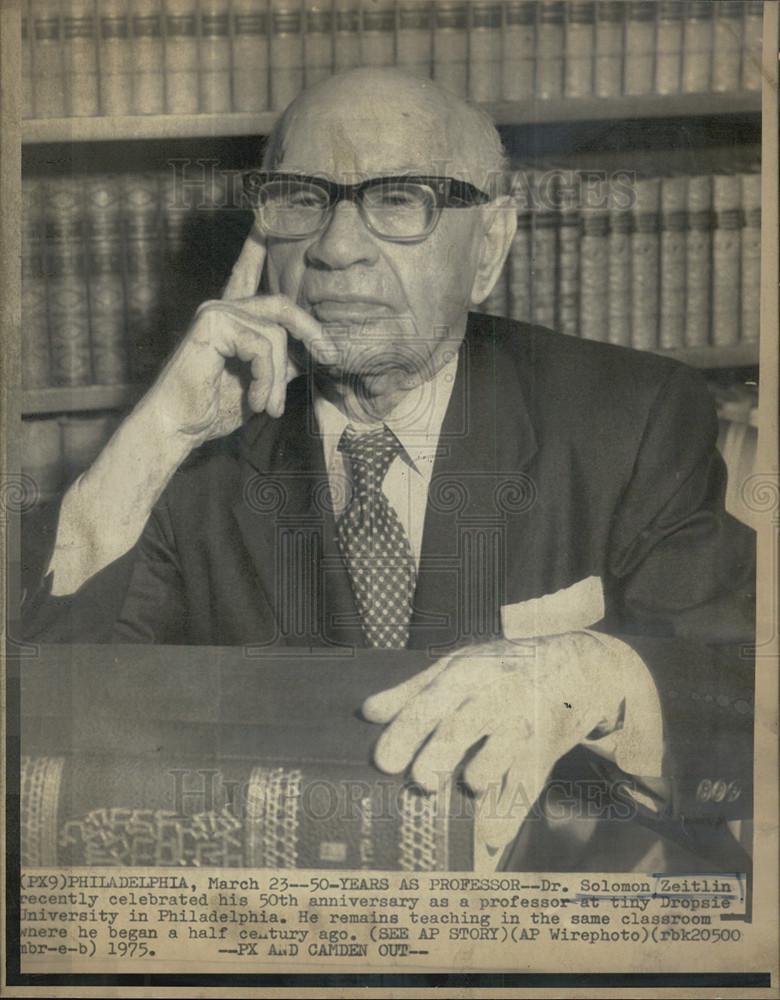

University of Chicago Archive

Norman Golb

Robert Eisenman also argued against the results of the carbon-dating that placed the composition of the Scrolls in the Maccabean period, and his interpretation of their content as being militant and zealous led him to date them to the late-Herodian era, which would means that the priesthood that they opposed was, in fact, the collaborating Herodian priesthood. He provided parallels between the political, religious, and ethical stance of these documents with the views held by James, the brother of Jesus, whom he identifies as the founder of the sectarian movement of Qumran37. However, if the Scrolls were of early Christian origin, it is strange that the figure of Jesus, the Christian Messiah, is missing from them.

Solomon Zeitlin, who constantly argued against the Second Temple dating of the Scrolls, put forward a few arguments concerning the dating of the Pesharim. As an example, he noted that they show familiarity with an Aramaic translation of the Prophets, the so-called Targum Johathan, dated to the 2nd century CE. Another example is the inclusion of matres lectionis (consonant letters that are used to represent vowels), which occurs frequently in the Scrolls but only came into usage during the time of R. Akiva153. He later concluded that most of the Scrolls should be dated from the early medieval period and belonged to one of the Karaite groups, who regarded Shammai to be their main religious authority152. While I cannot accept such a dating, I would agree that the style of the Pesharim can be compared to that of the Midrashic method that appeared in the 2nd century63.

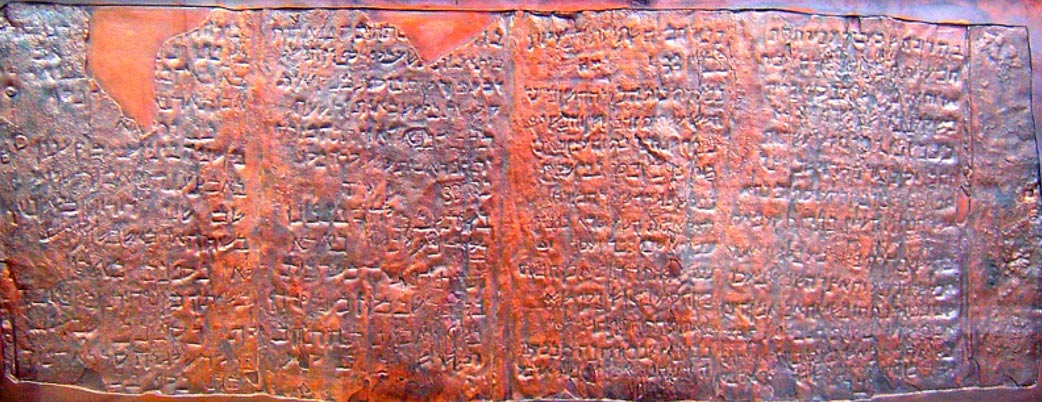

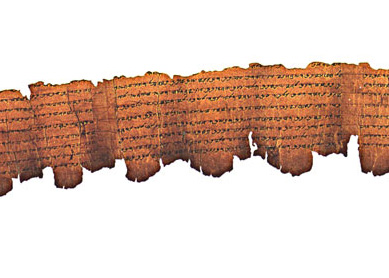

רשות העתיקות של ישראל Israel Antiquities Authority, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Cave of Letters

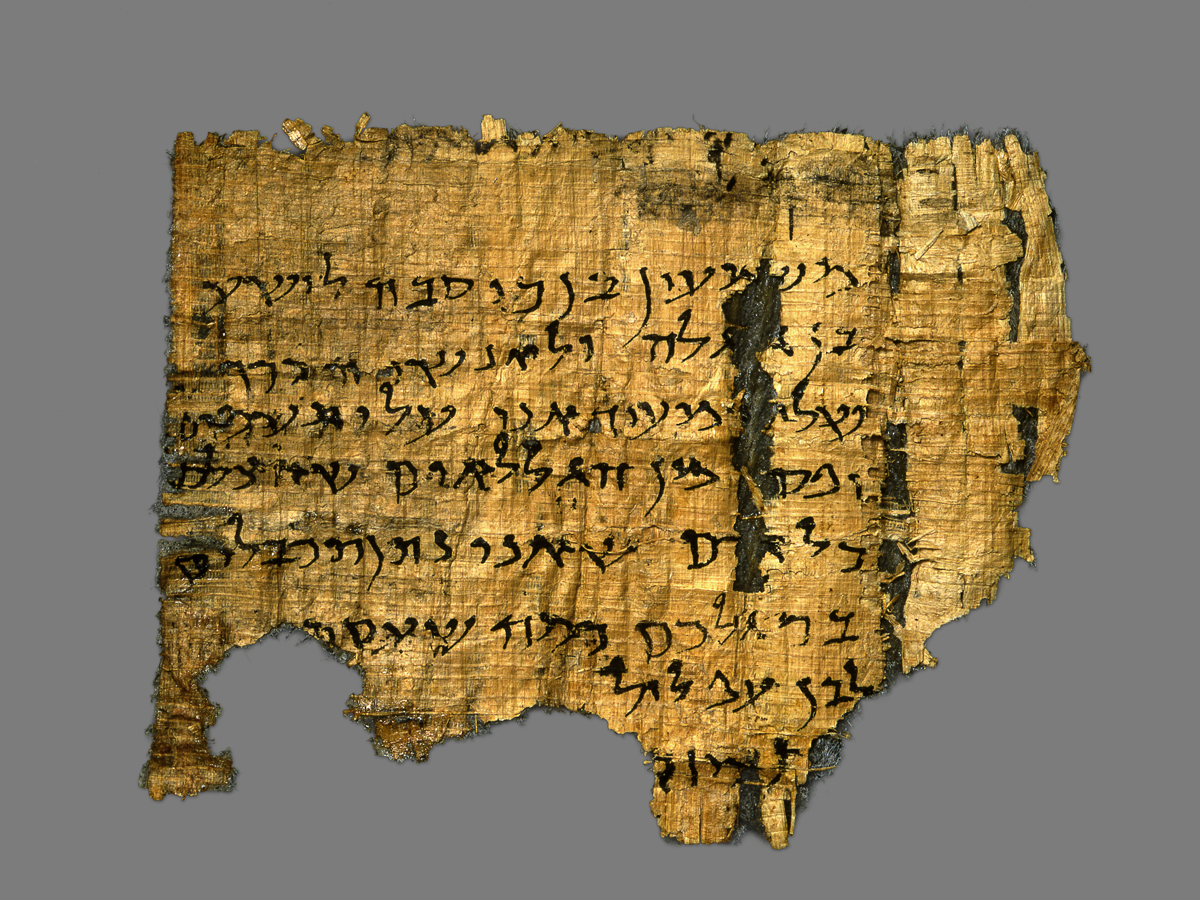

The first identification of the Scrolls as books from the Second Temple period was established on the basis of the similarities between the shapes of the letters they used and those appearing on the Jewish ossuaries with Aramaic inscription, discovered around Jerusalem. Importantly, no original Hebrew manuscripts that can be unquestionably dated to the Second Temple period were ever found; the documents from the Cave of Letters, as well as other finds, originating from Wadi Murabba’at, represent the earliest survived documents, written in the Hebrew language and script, and have been dated to the time of the Second Revolt62,149. Therefore, the paleographic arguments that the scholars attempted to substantiate while establishing the dating of the Scrolls within the Second Temple period, are irrelevant. Apart of that, some scholars have continued to rely on radio-carbon dating analysis of the Scrolls, which supposedly confirms their Hellenistic dating, however, various analyses demonstrate a very wide range of dating possibilities5. It is also interesting to note that many of the later calibrated dates, in fact, refer to the period after the hurban, with a wide range of dates lasting up until 118 CE, furthermore, some Scrolls, for example, the Covenant, could be dated up until 129. It seems important that the Cave of Letters, and the Caves of Qumran, were shown to be typologically similar in construction to other caves that were known to have been used by other groups of the supporters of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, for hiding from the Romans and also for keeping their precious valuables in140. The Copper Scroll described in details the whereabouts of valuables that had been accumulated by the rebels and then hidden in various locations in times of danger. The language of this Scroll is different from the rest of the sectarian documents, and it might be inferred that it was composed by the supporters of Bar Kokhba, who, after the suppression of the Revolt, decided to join the sect of Qumran.

2. Who were the Zadokite Jews?

Study of the Scrolls has shown that the religious beliefs followed by the sectarians differed from what we know of the ideas of the rabbis of Yavneh that were based on the traditions of the “House of Hillel” from the Second Temple period; at the same time their approach to the principles of Halakha was similar to that of their rivals, the “House of Shammai”. This inevitably raises the question as to which identity was maintained by the community that was responsible for producing the Scrolls. As both the Community Rule7,147 and the Damascus Covenant9,34,64, two highly significant sectarian documents of Qumran, refer to the founding members of the movement as the “Sons of Zadok, the Priests” (CD IV, 1,3; CR V, 1, 9; IX, 14), these two distinct treatises evidently relate to two very different stages in the chain of development of the rules of Halakha practiced by the Zadokite Jews.

The Community Rule (Serekh Ha-Yahad), also known as the Manuel of Discipline, appears to contain thoughtfully selected instructions that were drawn up to provide a regulatory framework for the life of a priestly community of the “Sons of Light”; it seems to reflect the earliest phase in the development of the sectarians’ ideas. The mention of the “priests” next to the “Sons of Zadok” suggests that their leadership mainly consisted of priests from the former Temple who, when they found themselves in exile, decided to establish the ascetic community of Yahad. Here they lived a rigorous lifestyle, denying themselves a family and abstaining from wine. In sharp contrast, the vibrant messianic community of the Covenanters had no wish to continue to impose such restrictions upon themselves any longer; they believed that although their ancestors had left the Land of Judah and fled to the Land of Damascus, they would return to their homeland in the “End of Days”64. The Covenanters also believed that their movement had been founded by a person named Zadok (CD V, 5), their eponymous founder, to whom all the “mysteries” of the world were made known and who had miraculously obtained these teachings from a “Sealed Book of the Law” (CD V, 2) that had been placed in the Ark of the Covenant before the time of King David. As the priest named Zadok was known as the High Priest of the Solomonic Temple, it was suggested that the founders of the sectarian movement were Sadducean priests who were his spiritual descendants and had served as priests in the Second Temple145. However, this theory has to be discounted as the Covenant explains that King David had multiple wives meaning that the “Sealed Book of the Torah”, which forbade polygamy, had not been revealed to him; it follows that it was only later, after this book was known to Zadok, the sectarians became aware of these laws (CD V,16).

Another possibility to consider is that Zadok was a historical figure from the end of the Second Temple period responsible for creating the anti-rabbinic tradition. The Karaite scholar, al-Qirqisani, who probably relied on a rabbinical work of the Geonic Era, Avot de-Rabbi Nathan, decided that the resistance to the rabbis started when Zadok and Boethus, the disciples of R. Antigonus, were “led astray”. He further attributed to Zadok the invention of a 364-day calendar and the concept of establishing holidays on certain days of the weeks instead of the months25. Additionally, he reported that Zadok, while criticizing the rabbis in his book, promoted the idea that a man should be prohibited from marrying his niece. It has been suggested that when al-Qirqisani claimed that he had the Book of Zadok in his possession, he might have, actually, been referring to a copy of the Covenant43, where similar ideas appeared and where the figure of Zadok was prominently highlighted; this might have led him to believe that it had been authored by Zadok. In addition, al-Qirqisani also mentioned “Maghariyya” (the “cave people”), who came after Zadok and owed their name to the fact that their books were discovered in a cave; these people have been identified as the sect of Qumran.

The Babylonian Talmud described the primary opponents of the rabbis during the Late-Antique period as the “Zadokim”, also referred to as “minim” (heretics) (Hag. 2, 4-5, Men. 10, 3). When examining various evidence from the Talmud relating to the controversies between the rabbis and the Zadokites, Richard Kalmin noted that the negative references to their opponents were probably not based on the old religious differences between the Pharisees and the Sadducees, but instead were meant to highlight the sectarian group that presented a serious alternative to the rabbis in the Late-Antique period75. Based on the differences between the rabbis and the Zadokites, Igor Tantlevskij showed that the Sadducees of the Second Temple cannot be equated with the “Zadokim” in the Talmud – firstly, because of their disagreement with the rabbis concerning the calendar, and secondly, on account of the dualistic character of their views. In his opinion, it would have been difficult to uphold these inconsistencies in the Second Temple, since the Sadducean priests, who were responsible for performing the sacrifices, would have been required to adjust the calendar in respect of the dates of the holidays139. This can be explained, however, if it is accepted that the traditionalists of Qumran used the priestly 364-day calendar advocated by 1 Enoch. In the same way that it is conceivable that the Pharisees of the Second Temple evolved into the rabbis, it is possible that the Sadducees also did not disappear, but instead the priests who left Jerusalem for Damascus evolved into the Zadokim; the cataclysm they suffered changed their attitude towards the strict monotheism and halakha.

The fact that the “Land of Damascus” was central to the early history of the Covenanters would seem to confirm the Syrian roots of the movement. According to John Reeves, there is a possibility that the Zadokite tradition flourished among the Syrian and Upper Mesopotamian Jews during the Late Antique period, which could explain why the Syriac literature appears to be especially rich in Pseudo-epigraphical ''survivals''117. In this regard, he cited a passage found in the Syriac text Vita Rabbula, a hagiographic work on Rabbula (411-35 CE), the Eastern Church leader responsible for the establishment of orthodoxy in the city of Edessa. In this text, its author identified a number of heresies that Rabbula suppressed upon his arrival in the city, including the mention of Zadokim alongside the Audians, a Gnostic dualistic group. In Reeves’ opinion, this was not accidental, and probably reflected the Christian attitude towards the Zadokim as Gnostics, which can be compared to the identity of the Manichean priests as “Righteous”116. It is interesting to note that the attitude of the rabbis towards the Manicheans was remarkably similar to that shown towards the Zadokim; Moshe Gil showed that the origin of the Talmudic term hanefim (“hypocrites”) used to describe the minim, is in fact relates to the Syriac term hanpe that was used to denote the Manicheans48.

Since the Talmud accused the Zadokim of being followers of dualistic views (Hul. 87a) and of “believing in the two powers in the sky” (Sanh. 38a), Kohler argued that these views were, from the rabbis’ perspective, similar to those of other dualistic groups (Ber. 58c; Shab. 88c; Ned. 49b), which is why they treated their writings, sifrei minim, in the same way as the Gnostic books (Sanh. 10a; 100b)80. The rabbis probably referred to the Zadokim as “Jewish Gnostics” on account of their dualistic views that were related to the concept of the Hidden Knowledge that was, apparently, disclosed to them, and the idea of the constant conflict between the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness as revealed in the Community Rule and the War Scroll. Although numerous attempts were made to explain this phenomenon being a result of Zoroastrian influence, it is worth noting that access to the Hidden Knowledge was a common claim amongst many Gnostic groups132. Since certain examples of the literature related to the Scrolls was preserved in the 4th century Gnostic library discovered in Nag-Hammadi, in Upper Egypt, it is probable that the Gnostics recognized the sect of Qumran as one of their own58. One text relates to the figure of the Priest Melchizedek, and refers to him as the Head of the Angels, who according to 11Q Melch, will “execute divine judgment” in the future eschatological Jubilee year88; another – an important Gnostic book named Three Steles of Seth contained the text entitled the Revelation to Dositheus.

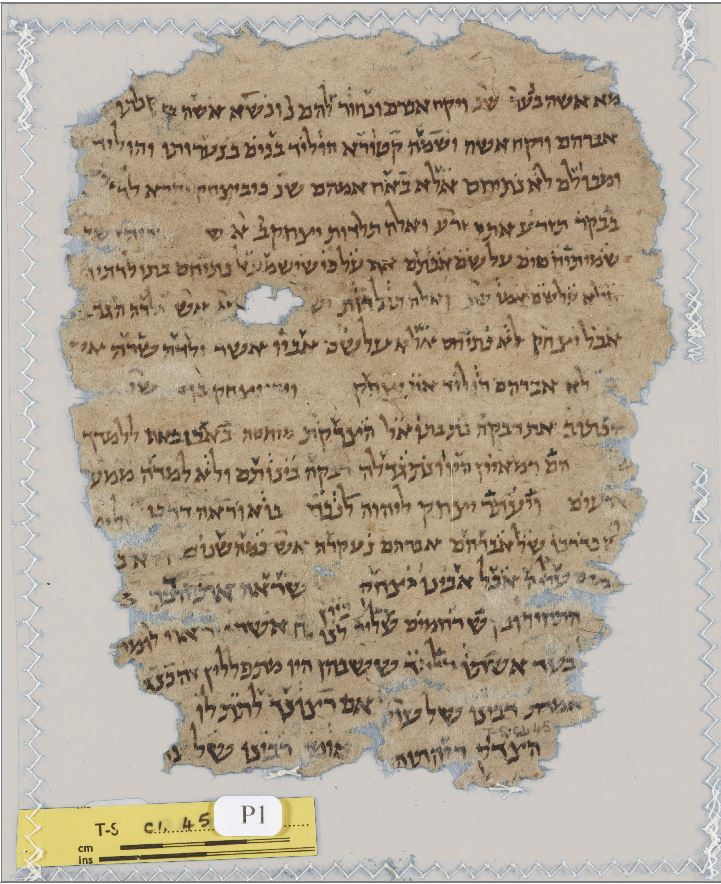

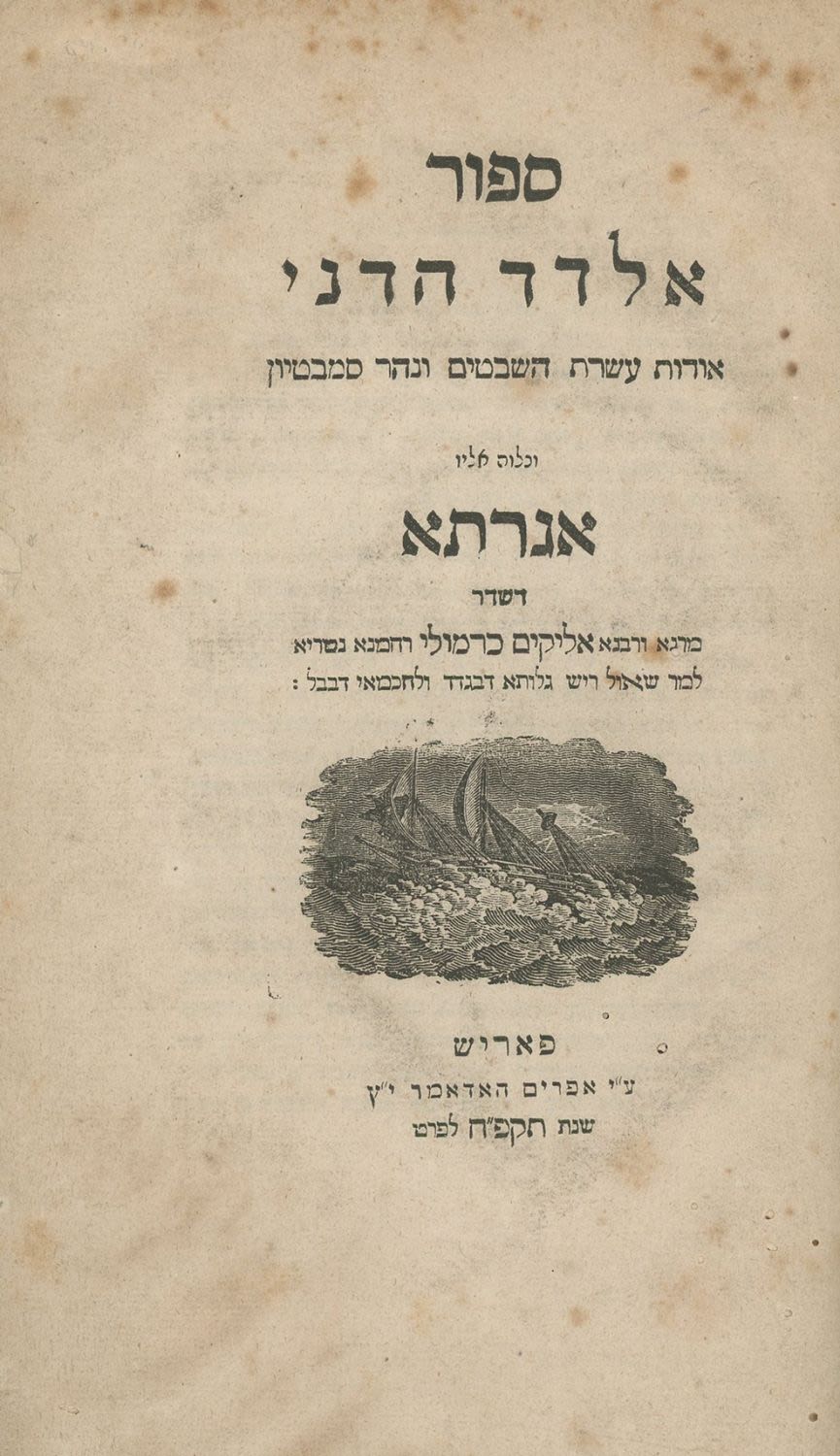

The historicity of the figure of Zadok, the eponymic founder of the sectarians’ movement, can be further reaffirmed if he is identified as Prophet Dositheus. According to the statements of Pseudo-Tertullian and Eusebius, he had been the founder of the sectarians known as the “Sadducees”, although it is probable that by these the Christian writers of the 4th century were actually referring to the Zadokim. The idea of identifying Dositheus as Zadok had already been proposed by Solomon Schechter; he had accessed two copies of the Damascus Covenant dated to the 10th - 11th centuries that had been discovered amongst the medieval Hebrew documents in the Cairo Genizah; and, in 1910, had published them as the Zadokite Fragments127. The 12th-century scholar, al-Shahrastani, reported that the Dositheans regarded their founder – who lived a century before Christ – as Ilfan (Teacher in Aramaic). Based on this chronological indication as well as evidence from the medieval Samaritan chronicle of Abu'l-Fath, who placed Dositheus in the time of John Hyrcanus, Schechter suggested that he might be considered a historical figure from c. 100 BCE. Abu'l-Fath relates that Dositheus was a Jew from Jerusalem, who, after his rejection at the hands of the rabbis, went to preach in Samaria; he was thrown out of Shechem by the local leaders, and spent his last days in exile writing his books in the house of a widow in a village of Suwaika.

PierreSelim, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Relief of Simon Magus at the gate of the Basilica of Saint-Sernin, Toulouse

In 1976, Stanley Isser issued his most comprehensive study of the Dositheans sect, where he argued in favor of a later, mid to late-1st century CE date for Dositheus70. He mainly relied on the dating provided by the Clementine Romance that was written in the 4th century by the Christians against the Gnostics. This dates the activities of Dositheus to the same time as those of Shimon Magus – a historical figure from the 40s CE, who opposed the Apostles (Acts 8:9-24), and was also often referred to as “the father of all heresies”. The Romance includes a story of a competition that arose between the two heresiarchs and tells how Dositheus, by spreading a false report of Shimon’s death, succeeded in installing himself as head of the sect. Upon his return, Shimon thought it better to dissemble, and pretending friendship for Dositheus, accepted second place148. The importance of this story lies not only in the fact that it provides evidence of Dositheus’ success in spreading his teachings among the Gnostics, but it also indicated a dating for his activities. It seems that the idea of the Gnostic influence in the Scrolls120,123 clearly contradicts their Hellenistic date since the dualistic views only became popular in Judea after Shimon Magus, unless, of course, we would like to claim that the Scrolls somehow preserved a “Jewish Gnosticism” before the rise of Gnosticism.

This chronology for the beginning of the sectarian movement can be confirmed by analysis of the chronological information recorded in the Damascus Covenant. The Admonition, a series of historical introductions to the Covenant, provides a valuable indication as to when the movement first came into being (CD I, 3-11). It dates its origins in the “period of wrath”, when “God hid his face from Israel and from his Sanctuary…three hundred and ninety years after they were delivered into the hands of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon”, he, however, “caused to sprout from Israel and from Aaron a shoot of the planting”, and twenty years later, “after they walked like blind” – the Teacher of Righteousness, finally, “rose up to lead them in the way of his heart”. In determining the chronology, the mention of 390 years has confused many scholars who have attempted to link this evidence with the exile in 586 BCE that had been ordered by Nebuchadnezzar II, thereby placing the roots of the Covenanters before the Maccabean revolt. One possible solution to this problem was suggested by Zeitlin, who pointed out that the chronology that was used by the rabbis was different from the modern one. According to the Seder Olam Rabbah, ch. 30, the Second Temple stood for 420 years, while the time between the fall of the First Temple and the building of the Second Temple was 70 years. Accordingly, Zeitlin arrived at the conclusion that the arrival of the Teacher of Righteousness should be dated c. 30 BCE, and that the dating of the conflict within the Jewish leadership could, therefore, be related to the time of the fight between the two important early halakhic authorities, Hillel and Shammai152.

In my opinion, a solution can be found if the reference to the actions of “Nebuchadnezzar”, in fact, relates to the plundering of Judea, which was carried out in the 340s BCE by the Achaemenid King, Artaxerxes III Ochus, whose identification was revealed through analysis of the Book of Judith; this describes the conquest of Judea by Nebuchadnezzar’s generals, Holofernes, and Bagoses. These characters have been identified as Orophernes, the Cappadocian satrap of Artaxerxes III, and his eunuch and general, Bagoas97. Additionally, Dan Barag’s analysis of archaeological evidence from Judea indicated a significant decline in the development of sites in the 340s BCE, thereby supporting this interpretation8. Applying the period of 390 years would bring the origin of the sect to the 50s CE; however, if the sectarian chronology differed from the modern scientific one, the Covenant’s reference that the “sprout from Israel” arose during the “period of wrath” would imply that the movement was established after 70 CE, and that the period of twenty years, when the sectarians “walked like blind” most probably referred to the turbulent period until the arrival of the Teacher of Righteousness.

The last part of the Covenant provides a key chronological indication as to the date of its final composition. It implied that there was a period of about forty years between the “gathering” of yoreh y-h-d, and the time when “all the Men of War who turned away with the Man of Lies (ish ha-kazzav) disappeared” (CD XX, 14-15) . In my opinion, the term *yoreh yahad, as it appears in the Covenant, was not an error of the copyist, but rather was intentionally used by the last editor of the Covenant, to distinguish this figure from more zedek, the Teacher of Righteousness. Taking into account that the indication of a Biblical period of “forty years” usually refers to the timeframe set for one generation, it can be concluded that the person known as yoreh yahad, who was identified as *more yahid – the “Unique Teacher” – or, more precisely, the “Teacher (of the Community) of Yahad”, is not identical to the Teacher of Righteousness. The Pesharim revealed that this latter figure was a contemporary of ish ha-kazzav – the Man of Lies, who is identified as Bar Kokhba, in line with the proposal firstly put forward in 1912 by Gresmann and Lagrange82. Thus, the Covenant related to a period of forty years between the death of the Teacher of Yahad, in 95 CE and the end of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, in 135 CE.

I believe that the identity of the sectarian leader known as * yoreh yahad can be discerned from information preserved by Abu'l-Fath, who recorded that Dositheus’s ideas were widely disseminated thanks to the efforts of his assistant, Yahdu. He came from the Samaritan village of Askar and was prominently regarded by Abu'l-Fath as a “very learned man, who was unique in his time in knowledge and in law”; he was an ascetic who did not drink wine and was very impressed by Dositheus’s explanation forbidding the eating of the firstborn of animals19. I would like to suggest that his personal name was probably recorded in the original title of the Community Rule – Serekh Ha-Yahad, where the ascetic ideas and teachings akin to those applied to Yahdu by Abu'l-Fath, revealed. It is possible that Yahdu was responsible for the Samaritan influence in the Scrolls that has become increasingly evident through recent research; indeed, scholars have realized the significant impact the Samaritans had on the formation of the sectarians’ library76. For example, Emmanuel Tov’s comprehensive study of the text of the Torah Scrolls of Qumran convincingly shows that, while not quite identical, they closely resembled the Samaritan rather than the Masoretic version of the Torah’s text142. The inclusion of the Tetragrammaton written in the Paleo-Hebrew (Samaritan) script, in the Pesharim, and the Psalms, is particularly notable; additionally, the Leviticus Scroll was entirely written in the same script61. It must be remembered, however, that this script which had been entirely forgotten during the Herodian period returned to usage during the Second Revolt.

The theory that the Covenanters should be identified as the Samaritan Dositheans was initially developed by Kohler79. He noticed that, although Dositheus, himself, was a Jewish religious leader of the Second Temple period, the importance of his figure during the Late Antique and medieval periods was primarily attached to the history of Samaritan sectarianism, and that the beliefs and traditions attributed to the Dositheans corresponded closely to what is known of the Covenanters . They anticipated the resurrection of their former leader and believed that he would reappear soon as the Messiah, son of Aaron and Israel (CD XIX, 10-11; XX, 1). According to Kohler, this priestly messianic concept was directly influenced by the idea of the old Samaritan priesthood descending from Aaron, and contradicted the rabbis’ concept that the Messiah would be descended from King David. After having studied the communal structure of the Covenanters and their various laws concerning Halakha, Kohler concluded that they were remarkably similar to those practiced by the Samaritan sectarians. The Zadokite identity of the sect of Qumran during the final period of its existence is reinforced by evidence from the medieval Samaritan chronicles. Abu'l-Fath related that among the followers of Dositheus was a group of “Sadukai”, who were referred to as “Zadduqim” in the Adler Chronicle; it was reported that “for seven years they practiced in a village named Maluf (“the place of teaching”) until the place fell upon them”19. Since no place with this name is known in Samaria, it is possible that it was a reference to Khirbet Qumran.

After the discovery of the Scrolls, John Bowman concluded that the 364-day solar calendar of Qumran was identical to the ancient Samaritan priestly calendar; he compared this to the fact that the Dositheans also used a solar calendar and counted 30 days each month18. He looked at the sacrificial rites of the Covenanters and noted a similarity in respect of the sacrifice of a red heifer that was described in the Song of the Sabbath Sacrific; he also noted that both groups demanded purification through water and constant bathing, and like the Samaritan Dositheans, the Covenanters had a requirement that anyone coming near a dead body must bathe before touching anything. All of this led Bowman to suggest that the strict requirements for ritual purity ensured that the sacrificial practices, which were forbidden in Jerusalem and on the Gerizim Mount, were permitted by the sectarians in Qumran. I believe, however, that these notable similarities between the practices of the Samaritan Dositheans and the Zadokites of Qumran should be considered as evidence of their possible common Dosithean origin, rather than proof that they should be identified with one another. It should also be noted that the Samaritans reported that there were various groups of followers of Dositheus60.

3. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus as the Teacher of Righteousness/ Interpreter of Law

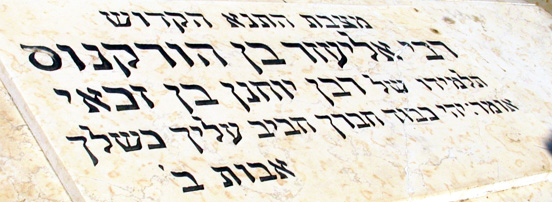

Public Domain

Eliezer b. Hyrcanus - Epitaph in Tiberias

The transformation of the Dositheans Community of Yahad into the Damascus Covenanters occurred following the great influence exerted by the person known as the “Teacher of Righteousness”, who appears to be the most significant figure in their history. This figure was unknown in the Community Rule, which was probably written sometime before his arrival in the sectarian community, but, a part of the Teacher, the Covenant also refers to the “Interpreter of the Law“ (doresh ha-torah), who “came to the captivity of Israel in the Land of Damascus and proclaimed the New Covenant” (CD VI, 5-8; VII, 18-19). An additional information on the figure of the “Teacher of Righteousness“ – otherwise named melits daat – “Interpreter of the Knowledge“, in the Pesharim, which using language that codified, but which may certainly have been understood by contemporary readers. For many years, scholars have argued over how to de-code the sobriquets of the Scrolls, while also trying to fix these hidden identities within the historical context of the Second Temple period and, indeed, there is still no consensus in respect to any of the endless proposals29. The identity of the leader of the sectarians, more zedek – the “Teacher of Righteousness“, is amongst the most debatable subjects in the current research of the Scrolls; as is his alter-ego, kohen ha-rasha – the “Wicked Priest“. Additionally, the identities of his opponents, a religious leader named mettif ha-kazzav – the “Preacher of Lies”, and a political and military leader, named ish ha-kazzav – the “Man of Lies” – have yet to be resolved. Controversy also surrounds the identification of the foreign invaders, the “Kittim”, or the “Kittim of Ashur”, as well as their powerful leader – the “Man of Belial”.

In my opinion, the sobriquets used in the Pesharim do not fit into the available database of the Hasmonean period, - not least because it is proving impossible to find a single timeframe that works for all of them. For example, in his book, "The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonaean State", Hanan Eshel identified the Teacher with Jonathan the Maccabee (161-43 BCE); the Wicked Priest with John Hyrcanus (134-04 BCE); and the Kittim – with the Romans, who invaded Judea in 63 BCE45. However, these attributions completely ignore the question of how all these different characters could have been present in Judea at the same time. In my opinion, these contradictions can be successfully resolved if we accept that the Pesharim should be regarded as a primary source for understanding the attitudes of the sectarians towards political events happening during the Yavneh period, from the Great Diaspora Revolt until the end of the Second Revolt.

I believe that in order to identify the enigmatic figure of the founder of the Covenanters it is necessary to look for relevant information in Talmudic sources. I would like to propose that this sobriquet, in fact, refers to R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus, one of the great lawmakers of the period, and a disciple of R. Yohanan b. Zakkai, the first leader of the Jews during the period after the hurban. At first, R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus was a respected member of the main Jewish religious authority, Sanhedrin of Yavneh, that was headed by R. Gamliel II, his brother-in-law49,103. He established his own academy at Lydda108, where he gained a reputation as a great scholar of law, with many important Jewish scholars, including R. Akiva, associating themselves with his school. He famously opposed the approach of Hillel and agreed with Shammai on the interpretation of the Halakhic laws and strongly objected to R. Akiva’s creative idea on their paraphrastic interpretation of the Midrashic works being presented as ultimate authority on religious practice. It appears that R. Eliezer was especially concerned about the issues related to ritual purity, and it is said that the last word he uttered was tahor(pure) (Sanh. 68a). He finally broke away from the Sanhedrin of Yavneh, on the issue of ritual purity related in the famous Talmudic story of the Oven of Akhnai (B. M. 59a-b). His refusal to submit to the decision of the rabbis, apparently, led to his expulsion from the Sanhedrin of Yavneh and excommunication from the Jewish community of Judea by the decision of Sanhedrin issued by R. Gamliel and reported to him by his pupil, R. Akiva6. Despite this, the Talmud continued to refer to R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus’s enormous contribution in the formulation of Jewish law, and he was referred to as Eliezer ha-Gadol (“Eliezer the Great”), or simply R. Eliezer.

It was convincingly shown by Vered Noam that the views expressed in 4QMMT and the Temple Scroll, especially those regarding ritual purity146 are practically identical to those associated with R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus in the Mishnah106. Furthermore, she decided that this phenomenon could be interpreted as the old cultural legacy of Qumran that later found its expression in the rulings of Halakha by the school of Shammai107, 108. It seems, however, that such an interpretation is difficult to justify, since there is no historical background behind the ideological influence that could cause an impact from the small sectarian group which supposedly remained in the quite seclusion of Qumran during the late-Hellenistic times on the major school of halakha which was developed in Jerusalem during the period of the 1st century CE. In my opinion, the rulings attributed to R. Eliezer in the Mishnah were original concepts that followed the general approach of the school of Shammai and that were initially set by this important Zadokite leader.

Some fragmentary remarks in the Talmud relate to the fate of R. Eliezer after his excommunication. It is reported that he was arrested by the Roman authorities on charges of heresy and put in prison; however, he was found innocent and released by a court decision131. The Talmud recounts, in detail, the story of how R. Eliezer, when appearing before the court, proclaimed “Blessed is the True Judge”; in fact, he was referring to God but the Roman judge, thinking that he was referring to himself, ordered him to be released (Hul. 2:24; A. Z. 16b-17a). Interestingly, when it was reported that he had been arrested by the Roman authorities on charges of minut - “heresy”, it was suggested by R. Akiva that this was due to his interactions with Yaakov, the “disciple of Joshua” (Hul. 2:24). It seems that these accusations were not far from the truth since the Covenant which reflected R. Eliezer’s ideas, revealed its author’s familiarity with Christian ideas, particularly the concept of the “New Covenant”. In fact, it seems unlikely that R. Eliezer sympathized with the Christians, and, more probably, he was charged because he was well acquainted with the books of Enoch, which were accepted as part of the Scripture by the Christians, but considered heretical by the majority of the rabbis.

The Thanksgiving Hymns of Qumran that were probably authored by R. Eliezer, confirms the authenticity of the Talmudic story of his arrest and recounts the period of his persecutions by the “men of Belial” (the Romans); he also complained that the false accusations provided to them led to him being arrested and imprisoned (1QH 13:5-39); other Hymns, however, praise God for his safekeeping, suggesting that he was later released from prison. It is probable that, after being excommunicated, R. Eliezer found refuge among the Dosithean community of Jewish exiles in Damascus where, through his efforts, they were introduced to the principles of halakha issued by the school of Shammai as well as to the innovative concept of the “New Covenant”. It would therefore seem that the Covenanters had its roots in the Jewish exiles who fled from Judea to Syria after the hurban; but, considering that they regarded themselves as “returnees” to the “Land of Judah”, this would suggest that they arrived back to their homeland under the leadership of R. Eliezer sometime shortly before the Second Revolt. While it can be inferred that the “Teacher of Righteousness” arrived to lead the sectarians in Damascus around 115 CE, about twenty years after the death of the “Teacher of Yahad”, in 95 CE, it remains unclear when he returned back to Judea. It would seem that he was still absent when R. Joshua b. Hananiah came to led the Sanhedrin and encountered Hadrian in 117 CE, although it appears that he was an extremely influential figure in Judea at the beginning of the Second Revolt.

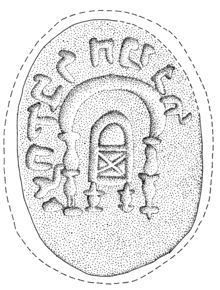

The name of Eliezer Ha-Kohen constantly appears on the silver and bronze coins struck with the inscription “First Year of the Redemption of Israel”, showing on the side with the cluster of grapes, with the palm tree with two bunches of dates on the observe94,96. These appears to be more common than the coins issued by Shimon Ha-Nasi (Bar Kokhba) in the First Year of Revolt; in addition, the name of Eliezer Ha-Kohen is rarely mentioned on the issues of Shimon Ha-Nasi coins from the 2nd and the 3rd year of the Second Revolt, and his name was inscribed upside down on these coins, having being directly copied from the older dies. Accepting that Eliezer Ha-Kohen can be equated to R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus, and taking into account that the title Kohen, “priest”, was applied to the Teacher of Righteousness by the Pesher Habbakuk (col. 2) as well as the Pesher Psalms (col. 2; 3), it can be concluded that he, temporarily, held the position of High Priest.

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bar Kokhba coin

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Eliezer ha-kohen coin

The traditional opinion is that Eliezer Ha-Kohen, who was regarded as the main religious authority during the Second Revolt, served next to Shimon Bar Kokhba, who was the military leader; this observation is based on the fact that their coins are typologically similar. Judging from the imagery on the coins minted by Shimon, his movement continued the efforts of Eliezer to secure liberation from Roman rule. Some of Shimon’s coins, minted in the 1st year, used the same symbols and slogans that had previously been inscribed on the coins by Eliezer96. In addition, on the coins struck from his 2nd and 3rd years, the image of the façade of the Temple appears next to the words “For the Liberation of Jerusalem”. This suggests that the rebels associated the concept of “Jerusalem” with an idea of the restoration of the Temple50. The diminishing of importance of Eliezer on the Shimon’s coins minted on the 2nd and 3rd years suggests that Shimon replaced him as leader of the Second Revolt. This probably explain why the name of Eliezer does not appear in any of the external sources on the Second Revolt, which were written during the period after its destruction, and which all consider Bar Kokhba as the only leader at the end of the upraise. Several questions can be asked here. Did the coins bear the image of the Temple as a reflection of the ideology of the rebels to restore it or construct a new one, or was it a depiction of an actual Temple? More intriguingly, it is very strange that only five of these coins were ever found in Jerusalem - does this mean that the city was, in fact, never captured by the rebels? Was Eliezer still alive when the Shimon’s coins were minted, or they postdate his time, which means that the dies of Eliezer’s coins were reused later? Finally, when and under what conditions did the attitude of the sectarians changed so dramatically towards Shimon that he started to be called the Man of Lies?

4. R. Gamliel as the Wicked Priest; the Rabbis as the Builders of the Wall; R. Akiva as the Preacher of Lies; Bar-Kokhba as Manasseh/ the Man of Lies

The Pesher Habakkuk explicitly refers to the period of persecutions of the sectarians initiated by the Jewish leader named kohen ha-rasha, the Wicked Priest; it related that “The Wicked Priest was called by the true name at the beginning of his standing, but when he ruled in Israel, his heart became large, and he abandoned God, and betrayed the laws for the sake of riches… and he stole and hoarded wealth from the brutal man…and he seized public money…” (1QpHab, col. 8). This statement would suggest that although the Wicked Priest initially intended to behave in a correct way towards the sectarians, his behavior changed dramatically due to the change in his status that resulted in him assuming political power and pursuing his opponent into exile; this remark corresponds to the initial period of close cooperation between the two Jewish leaders, while it also explains that it is only much later a major conflict arose between them. In my opinion, it is a reference to the confrontation between R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus and his brother-in-law, R. Gamliel II. The apparent change of heart of the Wicked Priest could have been a result of a change of the status of R. Gamliel that occurred after his recognition as the chief representative of the Jewish nation either after his visit to Rome at the end of the reign of Domitian, c. 95 CE, or during his trip to Syria to “gain permission” from the hegemon (M. Ed.7:7). At the time, the neutral title of Nasi (“Prince”) was accepted by R. Gamliel, who was probably the first Jewish leader to use this title officially.

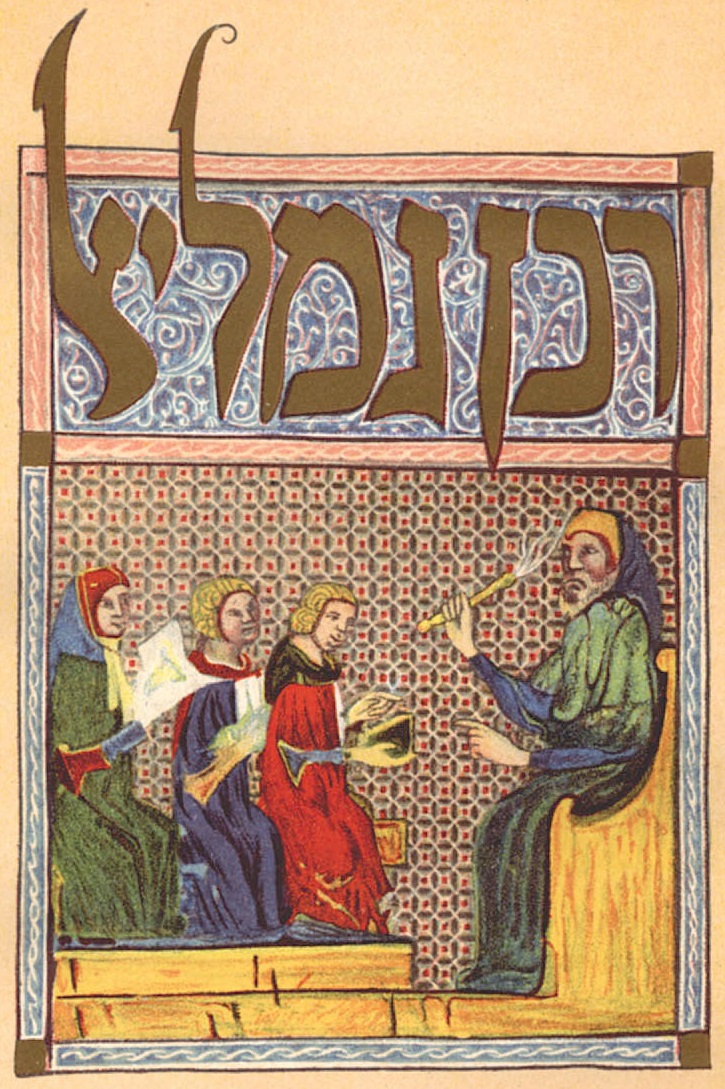

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Rabban Gamliel in a medieval miniature

R. Gamliel’s move to excommunicate his religious rival, R. Eliezer, may have been caused not only by religious, but also by political divergences. R. Gamliel’s main achievement was the unification of the nation, following the hurban, under the rule of the Sanhedrin of Yavneh, who embraced the principles of Halakha issued by the school of Hillel; this suggests that it was due to his dedicated efforts that all the various sectarian movements within Judaism were suppressed, and the Sanhedrin of Yavneh remained the only significant religious and political authority in Judea28. Apparently, the scale of the sectarians’ influence was significant enough for the rabbis of Yavneh to issue a special curse – Birkat ha-Minim – on the “heretics” that was purposely introduced into the prayer books as the twelfth of the Eighteen Benedictions of Amida, to deny any possible connection to the “heretics”83,141. It is probably because he had been appointed by Domitian, to collect the Jewish tax known as fiscus Iudaicus, that R. Gamliel was accused in the Pesharim of “accumulating wealth” and “robbing the poor people”.

The Pesher Habakkuk also refers to the “impure and abdominal deeds” by the Wicked Priest: he “performed repulsive acts in Jerusalem and defiled the Sanctuary of God” (1QpHab, col. 12). The reference to the state of sacrificial practices, which were considered ritually impure in the Pesharim is unlikely to be related to the situation pertaining in the Second Temple, but instead was a reference to the state of affairs during the Yavneh period. From the sectarians’ perspective, as the Temple in Jerusalem remained in a state of ruin, no sacrifices should have been offered there until the new Temple had been built122. The idea of building a Third Temple that came into focus of the ideology of the Second Revolt, found its expression in the Temple Scroll, the longest known sectarian document that was discovered among the Scrolls; it was written in the first person, suggesting that Moses had received it directly from the Angel on Mount Sinai151. Its author not only rejected the existing sacrificial practices as being “polluted”, but also provided detailed instructions as to how to conduct them properly avoiding ritual impurity; he also detailed plans for building a Third Temple in Jerusalem of vast proportions; its description was based on the dimensions borrowed from the Tabernacle of Moses from the Torah as well as Prophet Ezekiel’s vision. Some of the administrative and criminal laws referred to in the Temple Scroll relate to the revival of the Mosaic laws, but in order to apply these laws in reality, the Jews would have to achieve political independence; this implies that the Temple Scroll was composed after the independence of Judea was declared, and there were expectations that the Temple would be rebuilt soon. Taken this historical context into consideration, it is conceivable that R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus was the author of the Temple Scroll.

Since the title “Priest” normally referred to the High Priests of the Second Temple, it was thought that this was a reference to one of the Temple priests; but it must be considered that, during the entire Herodian period and until the hurban, the Sadducean priests maintained complete responsibility for the maintenance of the Temple, it seems highly unlikely, therefore, that the sectarians, who regarded themselves as the Sons of Zadok, would have opposed the Sadducean High Priests. There is, however, a good possibility that, regardless of the hurban, for a long time until the end of the Second Revolt, the Jews continued to offer sacrifices to the Temple’s altar27,59. Thus, the actions of the Wicked Priest suggest that it is likely that someone like Gamliel acting as the High Priest during the Yavneh period was responsible for sacrifices, but since he was not of a priestly lineage, he may have been referred, by the sectarians, as an “illegitimate”, “wicked”, priest.

Illustrator of Henry Davenport Northrop's 'Treasures of the Bible', 1894, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

High Priest Offering Incense on the Altar

By the time of R. Yehuda Ha-Nasi, the editor of the Mishnah c. 220 CE, the Jews had already been expelled to the Galilee, and the relevance of sacrifices that they were now unable to perform was now diminished, nevertheless, this book preserved a great deal of information regarding the opinions of various rabbis’ on the subject of sacrificial offerings. The Mishnah relates that when one of the last rabbinic leaders of the Yavneh period, R. Ishmael b. Elisha, who was named Kohen Ha-Gadol (High Priest), entered the Holy of Holies, and was asked by God for a blessing, he replied by asking God to treat Israel mercifully (Br.7a). This story shows him being in charge of the sacrificial rituals in the Day of Atonement and the text implies that, a part of the sacrificial altar, perhaps some sort of Sanctuary, existed in the Hadrianic period, and that R. Ishmael could have been serving as the High Priest of the Temple; it also implies that he might be in charge up until the time that Jerusalem evolved into Aelia Capitolina. During the early Yavneh period, however, the sacrificial rituals were supervised by R. Gamliel, and it is told that he ordered his servant to prepare lamb for a Passover sacrifice (Pes. 7.2); he is also reported to have visited the ruins of the Temple, accompanied by R. Joshua and R. Akiva, with the purpose of offering there (Sif. to Deut. 43)57.

The Pesharim explicitly refer to the period of persecutions of the sectarians which were initiated by the Wicked Priest. The Pesher Habakkuk relates that the Wicked Priest assaulted the Teacher of Righteousness in his place of exile, while visiting him on his “Day of Atonement” - Yom Kippur (1QpHab, col. 11). This story highlights a principle disagreement that arose between the two leaders in establishing the days of the festivals, which can only be explained if the sectarians used a different calendar from that of the rest of the Jews. In fact, R. Gamliel took the liberty of introducing a universal solar-lunar calendar into Judean practice, but this innovation did not pass without opposition within the rabbinic circles. It is reported that in a dispute about fixing the calendar, R. Gamliel humiliated R. Joshua b. Hananiah by asking him to show up with his "stick and satchel" (weekday attire) on the holy day which, according to R. Joshua's calculation, was Yom Kippur (Rosh Hash. 25a, b). This arrogant behavior led to the revolt by the rabbis against R. Gamliel, with the result that the Sanhedrin temporarily installed R. Eliezer b. Azariah as the new Nasi. R. Gamliel was later reinstalled, and probably retained his position until the events in Lydda that took place in 116 or 117 CE. At that time, all the Jewish leadership that remained in Lydda was removed by the Romans and many Jews were killed. The Talmud frequently refers to these events as the “slain of Lydda” (Pes.50a; B. B. 10b; Eccl. R. IX, 10).

It was reported in the Pesher Psalms, that the Wicked Priest was caught, and punished by the “wicked ones of the nations”, “for the wickedness against the Teacher of Righteousness and the members of his council God delivered him into the hands of his enemies to disgrace him with a punishment, to destroy him with bitterness of soul” (1QpPs, col. 9). It seems that this note leaves an impression that the persecutions of the sectarians occurred shortly before the tragic end of R. Gamliel during the events in Lydda; it means that the excommunication of R. Eliezer occurred c. 115 CE. This chronology better fits the remark of the Covenant relating to the “twenty years” period when the sectarians “walked like blind”, that passed between the death of the Teacher of Yahad and the arrival of the Teacher of Righteousness.

The Admonition of the Covenant completely ignores the figure of the “Wicked Priest”, but prominently highlights the primary ideological rival of the sectarians as the “Preacher of Lies” ( mettif kazzav); he “sprinkled upon Israel waters of falsehood and led them astray in a chaos without a way, bringing low the everlasting heights and departing from the path of righteousness, moving the border...surrendering them to the avenging sword” (CD I, 13-21; XIX, 25). He was considered responsible for the internal division that happened within the sectarian community: “he led astray many to build a city of emptiness with bloodshed and erecting a community by subterfuge for his own renown, wearing out many by useless work and by making them conceive acts of deceit…”(1QpHab, col.10). In my opinion, this figure might be identified as R. Akiva, the leading rabbinic authority on matters of Halakha in the time of Hadrian, and the only prominent rabbinic leader to support Bar Kokhba during the Second Revolt. R. Akiva began his studies in Lydda with R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus, but later founded his own school of thought in Beneberak; at the time of the conflict between R. Gamliel and R. Eliezer, he sided with the former. The Mishnah attempts to diminish the scale of the conflict that arose between the two leaders by relating that when the final decision to excommunicate R. Eliezer was taken, R. Akiva appeared before him in mourning clothes and, seated at some distance from him, addressed him with the words: "My master, it appears to me that thy colleagues keep aloof from thee". Because R. Akiva broke the news gently, it is told, R. Eliezer who had the power to destroy the world, annihilated no more than one-third of the crops worldwide and burned only those things that were within his field of view (B. M. 59b; M. Kat. 3:81a). Although it is reported that R. Akiva regretted not opposing enough his teacher’s excommunication and publicly mourned his death while accompanying his funeral procession from Caesarea to Lydda, crying outload and cutting himself (Sanh. 68a), this account appears to be a later reworking of the earlier version of the account in Y. Šabb. 2:5, 5b124.

The Pesher Nahum (4Q169 Frags. 3–4, col. 4.1) referred to a group identified as the “House of Peleg who joined Manasseh”. In addition, the Covenant (CD XX, 22) reports that “House of Peleg went out from the Holy City, and learned about God at the time when Israel sinned and defiled the sanctuary”; the Covenant suggested that these people were to be “judged individually”. Since the term “Peleg” originates from the Hebrew term meaning “to separate”, it can be assumed that this group was originally related to the sectarians but decided to separate from them at the later stage. It seems that the Pesher Habakkuk (col. 5) refers to the same group as the “House of Absalom”; they were accused of “keeping silent at the time of the reproach of the Teacher of Righteousness, and did not help him against the Man of Lies”. The use of the name Absalom was meant to evoke association with the Biblical figure of Absalom, the third son of King David, who betrayed his father. The Pesharim also consider them as “Traitors of the Covenant”, who were all expected to soon “perish by the sword, by hunger, and by plague” (4QPs, col. 2). This might be a reference to the great plague that came in the middle of the Second Revolt causing the deaths of twenty-four thousand followers of R. Akiva (Yev. 62b). The later Jewish authority, Rav Sherira Gaon, however, lists sh’mada as the source of their deaths, meaning that the students of R. Akiva who supported the Bar Kokhba Revolt, were martyred by the Romans; this event was referenced in the statement to those “who derided and went to the punishment of fire” (1QpHab, col.10). Following his capture by the Romans, R. Akiva was subjected to combing, a torture in which the victim's skin was flayed with iron combs (Ber. 61b) and died.

The Covenanters associated the figure of the Preacher of Lies with their main adversaries, a Jewish group who were referred as the “Trespassers” ( mesigei gvul). They arose “at the time of the destruction of the land, moved the boundary, and led Israel astray when the land became desolate”; the same group was also called by the Covenanters the “Builders of the Wall” (bonei ha-hets) (CD IV, 19-20; V, 20-21; VIII, 12, 18); they also complained that they did not accept their concept of monogamy that permitted a man “taking two wives during their lifetime” (CD IV, 20-21). In my opinion, this group cannot be identified as the Pharisees on account of a reference to their appearance during the period known as the “destruction of the land” (CD V, 20), suggesting that this was a reference to events that occurred after the hurban. This interpretation allows this group to be identified as the rabbis, the spiritual successors of the Pharisees; their unusual name may be a reference to the famous notion held by the rabbis, “building a fence around the Torah” (Pirkei Avot 1:1), in order to ensure the fulfillment of the Torah Commandments.

The Covenanters, who referred to themselves as “Judah”, and to the rabbis of Yavneh as “Ephraim”, declared their superiority over “Judah” during recent times: “Ephraim departed from Judah when the two houses of Israel split, Ephraim lorded over Judah” (CD VII, 12-13); in this way they evoked an association with the tragic split of the Samaritans, who believed to be descended from the Israelite tribe of Ephraim. It follows that the Covenanters recognized that, during the Yavneh period, the rabbis succeeded in convincing the Romans of their unique role as the deputies of the Jewish nation. According to the Pesharim, the adversaries of the sectarians, who were commonly associated with Jerusalem, were regarded as dorshei halakot – the “Seekers After the Smooth Things”. This name might have been an allusion to the “softer” attitude towards the matters of Halakha displayed by some rabbis, or, instead, because of their close corroboration with the Romans. During the Second Revolt, it is probable that the city of Jerusalem, itself, remained in hands of the Roman military, which was supplied by the Jews, who were opposing the Second Revolt, thus it seems likely that the Jewish population of Jerusalem aided in process of rebuilding the city before it finally turned into Aelia Capitolina.

Apart from a group of rabbis, commonly identified as “Ephraim”, the Pesher Psalms refers to another powerful group, known by the name of “Manasseh” that seemingly took their name from a historic tribe of Israel that was apparently coincident with the name of the ancient “idolatrous king” of Judea, Manasseh. Both of these groups had been blamed for attacking the leaders of the sectarians, and it was suggested that this would result in them being persecuted by the enemies: “The wicked ones of Ephraim and Manasseh will seek to lay hands on the Priest and the man of his counsel in the period of refining that is coming upon them. But God will ransom them from their hands, and afterwards they will be given later into the hand of the ruthless one of the Gentiles for judgment” (4QpPs, col.2). The ruler identified as “Manasseh” was in charge of Judea, but was destined to die or go into the exile: “Manasseh’s reign over Israel will be brought down…his wives, his children, and his infants will go into captivity… his warriors and his honored ones (will perish) by the sword” (4QpPs, col. 4). This seems to be a hostile prophecy to the fate of Bar Kokhba, the last Jewish ruler of Judea.

Despite Bar Kokhba’s association with the messianic “Star” prophecy from Numbers 18:24 generously granted by R. Akiva (Y.: Ta'anit 4:15), hence his nickname Bar Kokhba – the “Son of a Star”, in Aramaic – it was argued that the “Star” prophecy should be applied to their leader, the “Interpreter of the Law”; and it was only the “Scepter” prophecy that could be associated with the figure of “Nasi of the entire Congregation”, who was destined to lead them into the future decisive battle against their enemies, the Sons of Set (CD VII, 16-21)

Deror avi, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bar Kokhba (detail from the Knesset Menorah in Jerusalem)

From a historical perspective, the only time that a dual structure of supreme Jewish leadership can be observed was at the beginning of the Second Revolt71. From the original letters found in the Cave of Letters, it would seem that Bar Kokhba was regarded as secular and military ruler, but the coins also reveal that he was ruling alongside the religious leader, Eliezer Ha-Kohen95. The rabbis gave Shimon the pejorative name, Bar Kosiba – the “Son of Lies”121, while the Covenant and the Pesharim refers to him as the Man of Lies (ish kazzav) (CD XX, 14-15), who “led astray many with words of deceit, for they chose empty words and did not listen to the Interpreter of Knowledge” (4QPs, Frag. 1, col.1) and publicly confronted the Teacher of Righteousness, when the “Man of Lies worked against the Teacher of Righteousness and rejected the Torah (of the Teacher) in the midst of the entire Congregation” (1QpHab, col. 5). These quotes suggests that a conflict arose between the two leaders of the revolt that resulted in Eliezer Ha-Kohen being removed from power.

The initial approach of the sectarians towards the political situation pertaining in Judea at the beginning of the Second Revolt seems to have been supportive, and their books are full of expectations of the coming failure of the Romans rule. According to 4QMMT, the Halakhic Letter, also known as Miqsat Ma’ase ha-Torah (Some Observances of the Law), a disagreement arose between the sectarian and rabbinic leaders during the preceding era, resulting in them breaking away “from the multitude of the people”. However, they were now willing to join the common cause on condition that their views were accepted. The authors of the letter, who were referring to themselves in the plural form of “we”, recognized the legitimacy of the addressee, referring to him in the single form of “you”. Since they also compared his actions with those of the great Jewish kings of antiquity, David and Solomon, paying respect to his “wisdom and knowledge of the Torah”, so it seems that they believed that he must be regarded the rightful ruler of Israel. Nevertheless, the sectarian leaders still persuaded him to accept their ideas with regards to matters of ritual purity and the calculations of the calendar. In my opinion, the Halakhic Letter cannot be a private letter sent from the Teacher to the Wicked Priest, because the sectarians denied the legitimacy of the latter. Instead, it appears to be a letter that was probably written by the sectarian leaders, and its addressee was Shimon Bar Kokhba himself. Its authors hoped to convince their addressee to renounce the influence of the rabbis, who were not supportive of the Revolt anyway125, and instead, accept his authority in religious matters, but this appeal met with a negative response of Bar Kokhba, and as a result of his categorical rejection of the sectarian’s demands, the public conflict came about, which was referred by the Pesharim as a clash between “Judah” and “Manasseh”.

5. The Romans of Adiabene as the Kittim of Ashur; Emperor Hadrian as the Head over the Kings of Greece/ King Demetrius/ Man of Belial

The invasion of Judea by the “Kittim” provides the principle background for the historical events recorded by the Pesharim. According to the Pesher Habakkuk, the Kittim were a "cruel and determined people; swift and powerful in battle; destroying many with the sword; advancing quickly to destroy and pillage the cities of the country; trampling the land with their horses and with their beast; coming from the islands of the sea like an eagle; increasing their wealth with all their booty like the fish of the sea; sacrificing to their standards; their weapons of war are the objects of their reverence" (1QpHab, col. 2, 3). The majority of scholars agree that these particular characteristics closely resemble what we know of the Roman military, especially their association with an eagle, which was one of their symbols, and also the offering of sacrifices to their military standards. The Pesharim used the term “rulers” when referring to the chiefs of the Kittim, describing them as military leaders, who were “coming one after another to destroy the Earth” (1QpHab, col. 4); this is a reference to the commanders of the various Roman legions sent to Judea to quell the resistance.

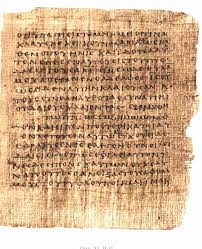

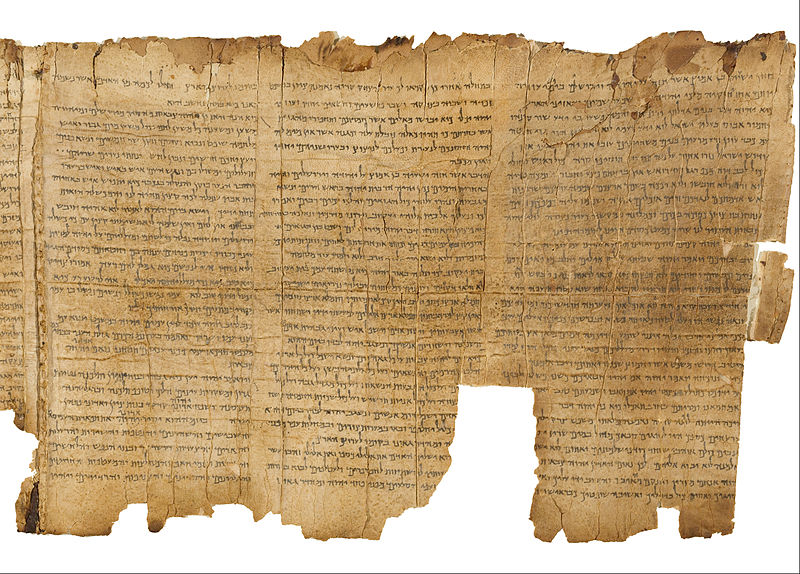

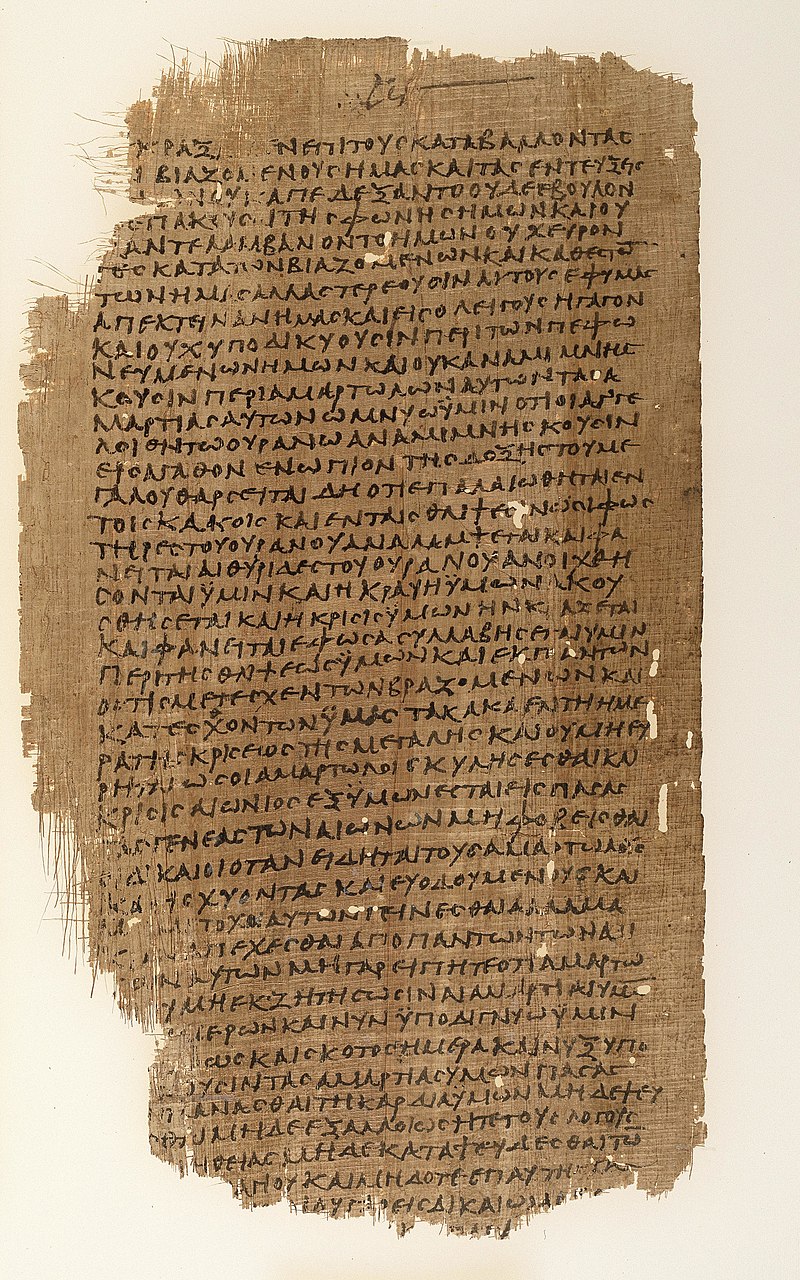

Matson Photo Service - American Colony Jerusalem, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The War Scroll - Dead Sea Scrolls

The War Scroll (1QM) provides detailed instructions for the organization of a Jewish army and reveals the tactics used by the rebels to fight their enemies; it “foresees” an eschatological war between the “Sons of Light” (bnei or) – the “Sons of Israel”, and the “Sons of Darkness” (bnei hosheh) – the Kittim of Ashur130. The straightforward identification of the Kittim in the War Scroll as the Romans raises the question as to why the Jews were unable to distinguish between an enemy who came from the west of the Mediterranean and one who arrived from the east; it also fails to explain their Assyrian identity, since the Biblical name Ashur (Assyria) was not normally used in Jewish literature to refer to Rome. Another proposal was to identify the Kittim of Ashur as the Seleucids, which would date the War Scroll to the 2nd century BCE; however, it was convincingly shown that the War Scroll contains a description of warfare that was similar to that used by the Romans150. The historical reference in Pesher Nahum (Frgs. 3-4, col. 1) differentiates between the Rulers of Kittim and Antioch, the King of Greece, effectively eliminating the suggestion that the Kittim of Ashur could be identified as the Seleucids. It was suggested that the term the “Kittim of Ashur” used in the War Scroll was a reference to the Roman army stationed in Syria, which in medieval times was occasionally referred to as “Assyria”, there is, however, no information in existing sources concerning any military resistance to the Romans in the territory of Syria either in 63 BCE or during the time of the Jewish Revolts.

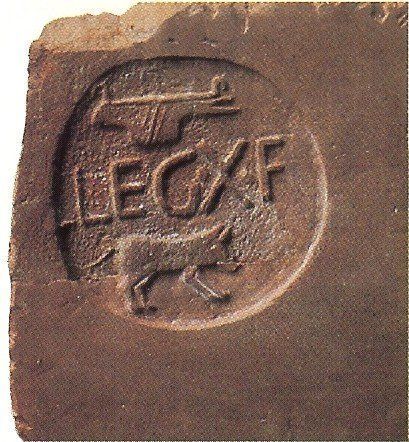

Lusius Quietus

Nevertheless, in my opinion, serious consideration should be given to the fact that, after Trajan conquered the Jewish Kingdom of Adiabene in 115-6 CE, he renamed it the “Roman Province of Assyria”, and proceeded to station Roman forces there. The great suffering of the Jews of Adiabene, and the rumors of the slaughter of thousands of Jews there, sparked the beginning of the Jewish Diaspora Revolt, that began in Libya and Egypt, before spreading to Cyprus, and later to Judea112. It is possible that the same Roman legions that were formerly stationed in Adiabene, were relocated to Judea in 117 CE under the leadership of the Roman general, Lusius Quietus, the conqueror of the Jews of northern Mesopotamia. After assuming command of the Roman army in Judea, Quietus laid siege to Lydda, where the rebels had gathered; when Lydda was taken, the rebellious Jews were executed. This theory can be further strengthened by the subsequent identification of the Kittim in Mitzraim (Romans in Egypt) – mentioned in the War Scroll as another enemy – as the Legio II Traiana Fortis stationed in Egypt. Apparently, in 1978, a milestone was discovered in the road that led from Acre to Sepphoris that attests to the presence of the Legio II Trajana there in 120 CE69.

The origin of the name Kittim, which would not normally be used by the late-antique rabbinic sources in respect of the Romans, is another subject of discussion. The Book of Daniel 11:30 mentions the “Ships of the Kittim” in relation to the military encounters between the Seleucid and Roman forces in the 170s BCE. Although this name was translated in the Septuagint as the Romans, and it was accepted that the Pesharim took this name from Daniel, it might also be derived from the Balaam’s Third Prophecy in the Torah (Num. 24:24). However, 1 Maccabees 1:1 clearly identified the Kittim as the Macedonians, claiming that Alexander the Great “marched out from the land of the Kittim”. Jubilees 37:10 describes that the army enlisted by the “Sons of Esau” to fight “the Sons of Jacob” included Kittim among its troops; scholars have regarded this as being a reference to the Greeks, but this is not at all certain. In my opinion, and as will be shown below, Jubilees itself was not a Hellenistic treatise, but it was composed in the Roman period, therefore its reference to the Kittim must refer to the Romans. Another possibility to consider, however, is that the unusual name of the Kittim only become popular during the events of the Great Jewish Diaspora Revolt when it was associated with the “Kitos War”, in turn, the name might have taken from Quietus, the main enemy of the Jews. This name, when it was cross-referenced with the Biblical term, was commonly used by the sectarian Jews from the beginning of the Great Diaspora Revolt and until the end of the Second Revolt.

Photo © Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by David Harris

Bronze statue of Hadrian from Tel Shalem in Israel Museum

The Pesher Nahum also mentions the figure of a military commander closely associated with the Kittim invaders – the “Angry Young Lion” (kefir ha-haron), and recounts dramatic stories of his cruel execution of the rabbinic Jews: "The Angry Young Lion struck (the simple folk of Ephraim with his nobles and the men of his counsel…brings vengeance on the Seekers After the Smooth Things…hang men up alive…filled his den with a mass of corpses…hanged men alive from the tree, committing an atrocity like never been seen before in Israel" (1QpNah, Frags. 2-3, col.1). The identity of the Angry Young Lion remains a mystery, and numerous identifications have been proposed; in my opinion, it seems very probable that the Angry Young Lion can be identified as Sextus Julius Severus, an accomplished Roman general, who was appointed by Hadrian to be a governor of Britannia68. He was subsequently transferred to Judea to help suppress the Second Revolt and was seemingly successful where all the others had failed. It was convincingly shown by Gregory Doudna that the figure of Angry Young Lion was portrayed in the Pesher Nahum as a military leader of the Kittim rather than a Jewish leader, and was considered responsible also for bringing an end to the rule of the “doomed ruler of Israel”, Manasseh36, in turn, I suggest that this leader should be identified as Bar Kokhba. His actions can be compared with the evidence of the Roman historian Cassius Dio 69:12-14, who relates that during the suppression of the Revolt, the Romans practiced mass punishment of the people, including crucifixion, razing villages to the ground and taking people into captivity. This proposal seems acceptable since a lion was a symbol of the Roman Legio XIII Gemina to which Severus belonged.

A.Savin (Wikimedia Commons · WikiPhotoSpace), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Arch of Hadrian - Athens

The Covenant explicitly referred to the figure of the chief enemy of the Jews, the powerful foreign ruler who was known as the “Head over the Kings of Yavan (Greece), who will come to wreak vengeance upon the dragon nations” (CD VIII, 10-12; XIX, 24). In my opinion, these references relate to Hadrian who replaced Trajan in August 117 CE; he was a philhellene who promoted Hellenistic culture in all the countries occupied by him, which is probably why the Covenant considered him responsible for introducing “Greek ways” into the cultural life of Judea. Hadrian was already appointed the eponymous archont of Athens in 112 CE when he was regarded as an ardent admirer, and a generous protector of Greek culture11. In 124 CE, upon his arrival in Greece, Hadrian assumed a commitment to the people of Athens; at their request, to revise their constitution and to rebuild ancient shrines; he also created new ones. To bring the Greeks together, in 131/2 Hadrian created a league of Greek city-states named the Panhellenion, and in this way he become the only Roman Emperor to assume the position of a “head over the Greek kings”.

Unlike the Pesharim, the Covenant did not use the name Kittim in connection with the enemies of the sectarians, but instead followed the approach of other Scrolls and associated them with the “Men of Belial” (“wicked”, or “worthless”); within the “three nets of Belial” it included improper sexual behavior, arrogance, and the “defilement of the Sanctuary” – the desecration of the Temple (CD IV, 17-18). In my opinion, this latter reference alludes to the activities of Hadrian, who, according to Cassius Dio 69.12.1, founded the city of Aelia Capitolina, in the place of Jerusalem, and erected the Temple of Zeus on the Temple Mount. The identity of Hadrian as the Man of Belial, who attempted to build the “wicked” city, is endorsed by the Pesher Joshua which refers to the Biblical curse of Joshua. According to this curse, the children of the Man of Belial, who would attempt to rebuild Jericho, would die: “At the cost of his firstborn he shall lay its foundation, and at the cost of his youngest he shall set up its gates” (Josh. 6:26), and he would then remain childless. This evidence was further confirmed by 4QPseudo-Ezekiel: ”A Son of Belial will plot to oppress my people, but I will not allow him to and his dominion will not exist, but he will defile a multitude, and his offspring will not remain” (4Q386, col. 2: 3-4). The Pesher Joshua also stated that being childless, the Man of Belial instead appointed “two men of violence” to succeed him but the first one died soon afterwards. Although Hadrian had no children through his marriage with Sabina, he appointed two of his adopted sons as his heirs, and they were both regarded as his co-rulers. In 136 CE, he adopted one of the consuls of the year, who took the name Lucius Aelius Caesar as Emperor-in-waiting; he died not long afterwards, on 1 January 138 CE. Later, in February 138 CE, shortly before his death in July 138 CE, Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius who succeeded him as the new Emperor.

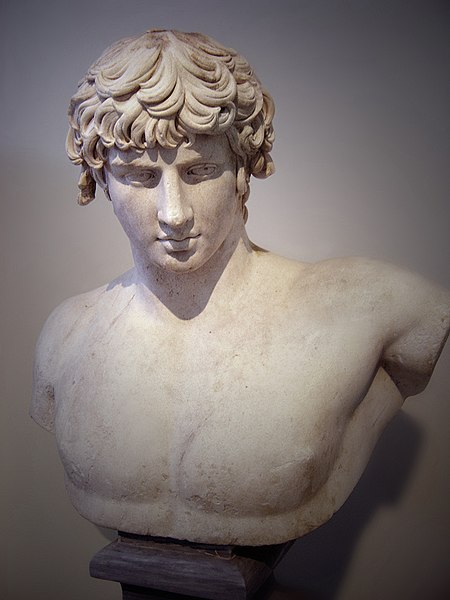

Ricardo André Frantz (User:Tetraktys), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Antinous's marble portrait

The Scroll referred to as 4QPseudo-Ezekiel reports the death of the person identified as the “Wicked One who will be slain in Memphis” (4Q386, col. 2:6). This event was confirmed by statement of another Scroll, the Psalms of Solomon: “his body was carried about on the waves in great shame and there was no one to bury him”. Such an unusual description of the death of the Wicked One probably describes the sudden tragic death of Antinous, Hadrian’s favorite and lover, who committed suicide during their joint trip to Egypt in late autumn 130 CE by throwing himself into the waters of the River Nile. His death severely affected the spirit of Hadrian, who created a cult around him naming temples after him and a city in Egypt. Considering that the identification of the events mentioned in these references is correct, it might be inferred that the Scrolls continued to refer to the events during the last years of Hadrian’s reign for a long time after the failure of the Revolt.

The statement in Pesher Nahum (Frags. 3-4, col. 1) that “Demetrius, king of Greece, entered Jerusalem on the counsel of the Seekers After the Smooth Things” confused many scholars since it also stated, in the same passage, that no foreign king had ever entered Jerusalem since the time of Antiochus up until the rise of the “rulers of the Kittim”. Since the figure of Antiochus could only relate to the Seleucid king Antiochus VII Sidetes, who captured Jerusalem in 134 BCE, it has not been possible to provide an identification for “King Demetrius” within the Hellenistic period. This information appears to allude to the first visit of Hadrian to Jerusalem, which almost certainly took place in agreement with the rabbis. This suggestion can be further strengthened by the accusations of the corroboration of the rabbis with the Romans made by Pesher Habakkuk (col. 4); it reports on the conspiracy with the Kittim, who advanced “on their counsel”; according to the Pesher Nahum, the Kittim came “on the counsel of the Seekers After the Smooth Things” (Frags. 3-4, col.1). In my opinion, this group can be identified as the followers of R. Meir, which at first stayed in Jerusalem where they supplied the Roman Legio X Fretensis but remained abroad during the Hadrianic persecutions.

It was probably during this visit that Hadrian decided to entrust the reconstruction of Jerusalem to the Greek intellectual, Aquila of Sinope, who translated the Bible into Greek, and made tempting promises to the rabbinic leaders in regard to the rebuilding of the Temple. The Talmud reports that when Hadrian arrived in Jerusalem for the first time, he was particularly supportive of the rabbis’ idea of rebuilding the Temple. He apparently promised R. Joshua b. Hananiah, the new leader of the rabbis, who had accompanied Hadrian during his trip to Egypt (Hul. 59b) that this would be accomplished soon (Gen. Rab., LXIV, 10). The author of the Epistle of Barnabas XVI, 4, who strongly rejected the prevailing sacrificial practices of the Jews, also seems to indicate that there was an expectation that the Romans would rebuild the Temple68.The Talmud relates that when one of the last rabbinic leaders of the Yavneh period, R. Ishmael b. Elisha – who was named Kohen Ha-Gadol (the High Priest) – entered the “Holy of Holies”, God asked him for a blessing, he replied by asking for God himself to treat Israel mercifully (Br.7a). This suggests that R. Ishmael was in charge of the sacrificial rituals on the Day of Atonement and that, shortly before the beginning of the Second Revolt, perhaps some sort of a Jewish Sanctuary on the Temple Mount already existed. The sectarians opposed to such minor construction, and initiated a campaign for it to be desacralized, since they maintained that a great Temple of enormous dimensions should have been erected, exactly as specified in the Temple Scroll.

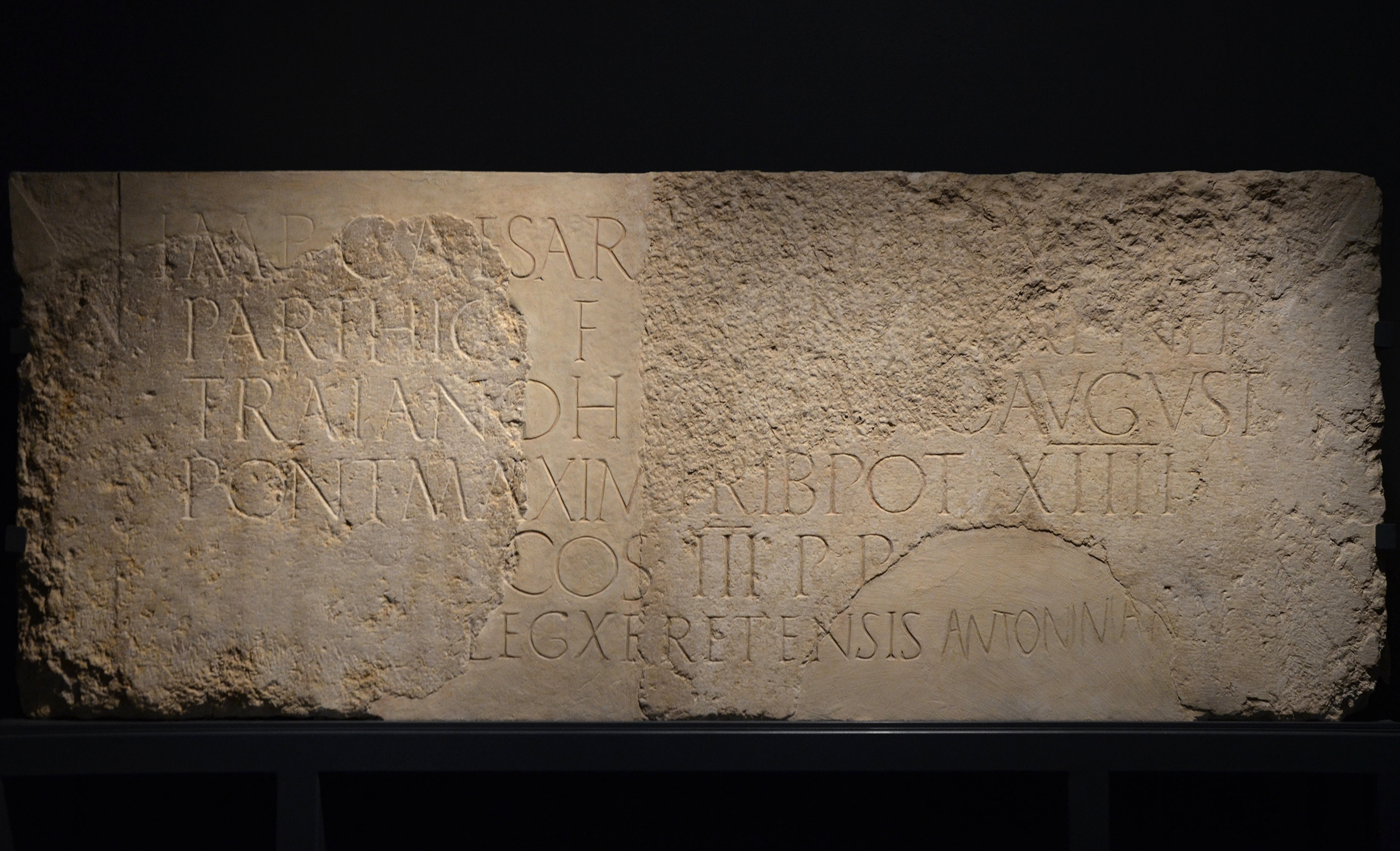

In 2014, when the Israel Antiquities Authority conducted salvage excavations in Jerusalem in several areas north of Damascus Gate, a stone fragment bearing an official Latin inscription of six lines was discovered, containing a dedication by Roman Legio X Fretensis to Emperor Hadrian on the occasion of his visit to Jerusalem: “To the Imperator Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, son of the deified Traianus Parthicus, grandson of the deified Nerva, High Priest, invested with tribunician power for the 14th time, consul for the third time, father of the country (dedicated by) the 10th legion Fretensis Antoniniana”. Interestingly, this inscription portray Hadrian, as the High Priest. The rabbinic text Exodus Rabba 61:5 also points to the active participation of Hadrian in the Temple’s sacrificial rituals, as it says: “R. Shimon ben Yohai said: When Hadrian entered the Holy of Holies…” The date of Hadrian’s famous visit to Jerusalem and of his actions that potentially caused the rebellion, is traditionally established as 129/130 CE, when Hadrian went on a “Grand Tour” on the Roman Near Eastern provinces. However, no precise dates were given by the Roman historian Cassius Dio 69.12.1-2, who is the main external source of our information, although he did connect the beginning of the Second Revolt with the consequences of Hadrian’s visit to Jerusalem22. This dating was recently challenged by Livia Capponi, who suggested that, instead, the first visit of Hadrian to Jerusalem could have occurred before his trip to Alexandria, in August or September 117, soon after his installment as Emperor in 11th August 117 CE21.

Information contained in the Scrolls sheds a new light on the events of this period and allows us to reevaluate its dating as well as reassess the reasons for the visit, as well as the context behind the Second Revolt. The Scroll labelled 4Q248 is a remnant of an apocalyptic work which tells of the actions of a “Greek king”, who visited Jerusalem following his brutal treatment of the population during the siege of Alexandria. A connection was made with the beginning of the rebellion in Judea following the visit of this king:”…and he shall rule over Egypt and Greece, and (against the God of Gods he shall exalt himself). And so they will eat the flesh of their sons and daughters in siege at Alexandria…and he shall return from Alexandria (and) come to Egypt and sell its land, and he shall come to the Temple City and seize it and all its treasures, and he shall overthrow lands of (foreign) nations and (then) return to Egypt. And when the breaking of the power of the holy people comes to an end… (and) the Children of (Israel) shall repent.”20